Read Part 1 of this series here. It will give you background on the story of the girls that this backstory is dependent upon.

The room was dark — there was no electricity and only diffuse sunlight seeped through the windows. Mothers, a couple of fathers and a handful of children were scattered around the floor. Some cried, others rocked. Some kept their eyes fixed on the ground. Some were furious.

I spent hours in that room speaking with the parents of a handful of the 40-something young girls who’d been abducted and raped in Kavumu over the past three-and-a-half years. In a closet-sized space just off the main area, I interviewed nine of the girls, one by one.*

This was a gathering I badly needed to have in order to tell this story properly. And it nearly didn’t happen because of various difficult ethical decisions I didn’t know how to make.

Before I left New York for the Democratic Republic of Congo, I tried to organize a way to meet with the little girls and their families, knowing that hearing what had happened to them in their own words was critical.

I knew that these children and their families had little to no access to a free media, and that even if they did, they’d likely be killed for speaking to reporters. But they were the only ones who knew what they’d lived. They weren’t mute, just scared.

The phrase “giving voice to the voiceless” has always irritated me, but I could never put my finger on why exactly. A few years ago, Margot Wallström, Sweden’s former minister of foreign affairs, put what I was feeling into the right words: “No woman needs to be ‘given a voice.’ Everyone has a voice. What is needed is more listening.”

And by then I was willing to do whatever I could do as a journalist to get the Congolese government to pay attention to these atrocities. Listening was a start.

So, from New York, I asked a friend in the eastern Congolese city of Bukavu (near Kavumu) to see if she could help set something up with the families. She found a friend of hers who said she would make the meeting happen — for a price.

As I said in an earlier part of this series, this trip was expensive and costing more than I was going to be paid by The Guardian, which had agreed to run a long-form article. (Eventually, wonderfully, the Women’s Media Center funded much of my reporting.) This friend of my friend wanted $500 to organize the families, saying she’d give some of it to them. The amount was extremely high in a place where people make on average only $394 a year, according to a 2015 analysis by the International Monetary Fund. (To be clear though: A broken economy doesn’t mean people shouldn’t make a much better wage when foreigners hire them. I hate that attitude — that Westerners should pay as little as possible to people in a place of extreme poverty).

But on top of my scarcity of funds, it is one of the fundamental rules of journalism that you do not ever, under any circumstances, pay your sources. (Or take gifts from them, a lesson my first journalism professor drilled into me with a blunt bit when a lovely old man I interviewed at his jewelry store in the Bronx insisted on buying me a bagel and coffee, and I let him. Gasp.)

Paying sources means you can’t know whether they’re telling you the truth, or just what you want to hear, among other things.

But the trip was getting close and I was beginning to panic, having no access to the families and knowing that I couldn’t just walk into a village besieged for years by the gang rapes of tiny girls and wander around asking to talk to them. It’d be dangerous for me, sure, but so much more so for them. That was one of my biggest fears about this reporting trip, that I would endanger everyone I spoke to just because they chose to talk to me, a foreign journalist. That was certainly the case in my years of reporting on Syria, but those are stories for another time.

I called an old colleague — a super talented and experienced journalist — for advice. He’d been a bureau chief in West Africa, Israel and elsewhere for one of the world’s biggest wire services. I told him I didn’t know what to do without this woman’s assistance but knew I couldn’t pay her.

He explained that in some countries you can bring people small things like cooking oil, or flour, to show your respect. And yes, this goes against what I wrote above about gifts, but in countries where most journalists pay their sources, as in DRC, this felt doable and unlikely to cause harm. Still, I didn’t love the idea, or even know whether it would work.

So I went to Congo without a real plan. But, as in all reporting, one interview or source leads to the next, and I lucked out in meeting early on a couple of extraordinary women from a nonprofit Spanish primate rescue group called Coopera. Their office was in Lwiro, near the plantation I wrote about in the last part of this series. One of them was a psychologist in addition to her job at the center and had been providing the families in Kavumu group therapy.

Before I really knew her, one of the women agreed to help me. But, she explained, she couldn’t ask the parents to take time away from their work to meet with me — they couldn’t afford to lose the dollar or less a day of earnings. I’d have to compensate them for their time.

I was crestfallen. That was it then. I could not pay my sources. But my heart was pounding and I felt unable to leave the cramped office until I figured out what to do. Finally, I told the woman, whom I’ll call Sofia since I haven’t asked her recently whether I can use her real name, that she was my only hope. I really, really needed her help. Wasn’t there any other way? Please?

No, unfortunately. It seemed there wasn’t.

Frustrated, upset and vaguely freaking out, I finally asked her how much money she would need to make up the pay the parents would be losing to meet with me.

Her answer?

Ten dollars.

Yes, $10. Ten. Not $10 for each person, just $10 in total.

This small amount of money was all that stood between me and this extremely important meeting. Then I had an epiphany.

Coopera was a nonprofit. I could make a donation to a nonprofit, even just a small amount like, say, $10.

I pulled out a bill stained red by the country’s ubiquitous rust-colored dirt and gave it to Sofia.

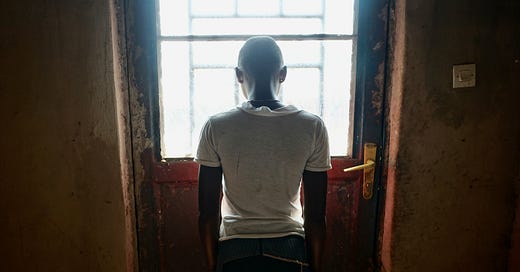

Gloria was a lanky girl who wore a polyester skirt-and-blouse set straight out of the 1970s. Her hair was shorn close to her head, like those of the eight other girls gathered that day at the end of 2015. The mothers all had their heads covered with plain hats or scarves. And for some reason, one of the women was wearing a Santa hat.

I spoke to Gloria in the tiny room off the main one. Her father, Alain, was present. (All the other girls had their mothers there when we spoke in private. They were all under 13 years old.) There was only one window, murky, which framed a view of laundry lines and tumbledown shacks.

Gloria whispered her story into her lap as somewhere nearby a goat kept bleating.

The night she was taken she was 10 years old. A man entered her kitchen, which was just outside her house, terrifying her. She tried to yell, “but when I wanted to shout, he took a cloth and put it over my mouth,” she said.

The man took her to a house with an empty room.

She was discovered missing by her mother, who then sent Gloria’s older brother to look for her. While searching, he heard noises that he described as sounding like legs hitting the walls of one of the village’s shacks. He looked through the gaps of the outer wall’s wooden slats and saw the unthinkable: There was a half-naked man on top of his little sister.

Soldiers arrested the rapist with his pants around his ankles. As had happened with other families, they also arrested Gloria’s father, but soon released him without charge. The perpetrator, according to her father, bought his way out of jail for $400.

None of the other girls I spoke to that day were found in the middle of their assaults — nearly all had been found after the fact in a field farmed by demobilized soldiers. But, like the others, Gloria was still struggling day to day with a trauma that was never far from the front of her mind, even nearly three years later.

Throughout our time together, I saw some of the girls smile shyly or even light up. But they inevitably shuttered their faces, hung their heads and fidgeted with their hands. Some went still and drooped, almost as if they were comatose.

Before I said goodbye to Gloria, I asked her what she hoped would happen to the men who had raped her and the other girls. In a barely audible voice, she said, “God will punish them one day.”

She may have been on the right track: Requests for justice, I realized, may have needed to aim that high — it’s not like the government was doing anything. Or so I thought.

One girl, whom I’ll call Rose, had been kidnapped and raped twice the year before, when she was 11. Rose’s almond eyes were hesitant as she described how she felt weak and startled easily. She picked at a mosquito bite as she pleaded: “Help us find somewhere — even 2 meters square — where they can build us a place that’s safe. I fear that if I go back home to my own house, I will die.”

Some of the parents told me that they thought the attacks were an organized effort by the government to extort the villagers. In most of the assaults, the men had worn black balaclavas. At one point, the police heard that Alain had been keeping notes and recordings on each case. Officers showed up at his house demanding that he hand over his audio and written notes. They were wearing black balaclavas. Also, in a bumbling move, one attacker had dropped a police hat in Alain’s house.

Adding to suspicion that police or the FARDC (the Congolese army) may be behind the horrors, the women and men gathered told me that they had zero trust in Kinshasa.

“The government doesn’t care about what’s happening here,” said one mother, wrapped in green. “It’s like it’s normal.”

“What can you say?” Alain asked, tears streaking down his cheeks. “There is no government in the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

I would soon learn, however, that a single police officer had been slowly making progress in his investigation, and was treating the dozens of rapes as a single case, which international groups like Physicians for Human Rights and TRIAL International had been advocating for.

I’ll tell you about him soon. I’ve been very, very excited for that because finally, after nearly five years, the officer has given me permission to name him. The last time I used his name publicly (with his permission at the time, but I’ll explain what happened in an upcoming piece), it was a disaster that nearly got him killed and landed me in the hospital with stress-related abdominal pain.

It was not the first — and far from the last — time my sources in Kavumu would be threatened or nearly murdered.

In the meantime, just know that by the time I met all of these extraordinary people, these survivors, these heroes, much of the village was on alert, and traumatized. No one in Kavumu slept anymore.

Coming in Part 6 (or maybe another part after that): You’ll meet the police officer who risked everything to stop the rapes, and hear more from the girls themselves. I’ll introduce you to the medical workers who performed surgeries on the children, and to others who dedicated themselves one way or another over years to making sure these crimes came to an end.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

*I don’t put trigger warnings on my stories about Kavumu, because it’s all nightmarish. But please be aware that there is a graphic depiction here of the rape of a child.

Thank you for another post in this fine series. I find that I am learning so much, not only about the trials of the youngs Congolese girls who were abducted and raped, but also about the trials of a reporter struggling with ethical concerns while trying to get her story out.

Although both sides of this kind of story deserve further treatment, the question of what price reporters pay for access to sources is both more universal and often much less explored. This is especially true with the coverage of high-level political leaders where hobnobbing and other implicit quid-pro-quos far exceed $10 in value.

Suffice it to say, you have given us a close look at the real ethical challenges faced by journalists and not the fabricated ones that have lately garnered more attention. I also want you to know that I am listening.

As always, riveting. Still don’t understand how nobody heard the intruders abducting the girls. Hope Moose is having a good day.