How a journalist chases a monster, Part 2

Walking into a war zone where a bunch of madmen are raping little girls.

Read Part 1 of this series here. It will give you background on the story of the girls that this backstory is dependent upon.

My fixer and I sat in a darkened shack in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. With no electricity, there was only the smeared daylight that came through a filthy window, but, more important, there was no fan. And this tight, humid space smelled strongly of the sweating official sitting at the child-sized desk in front of us.

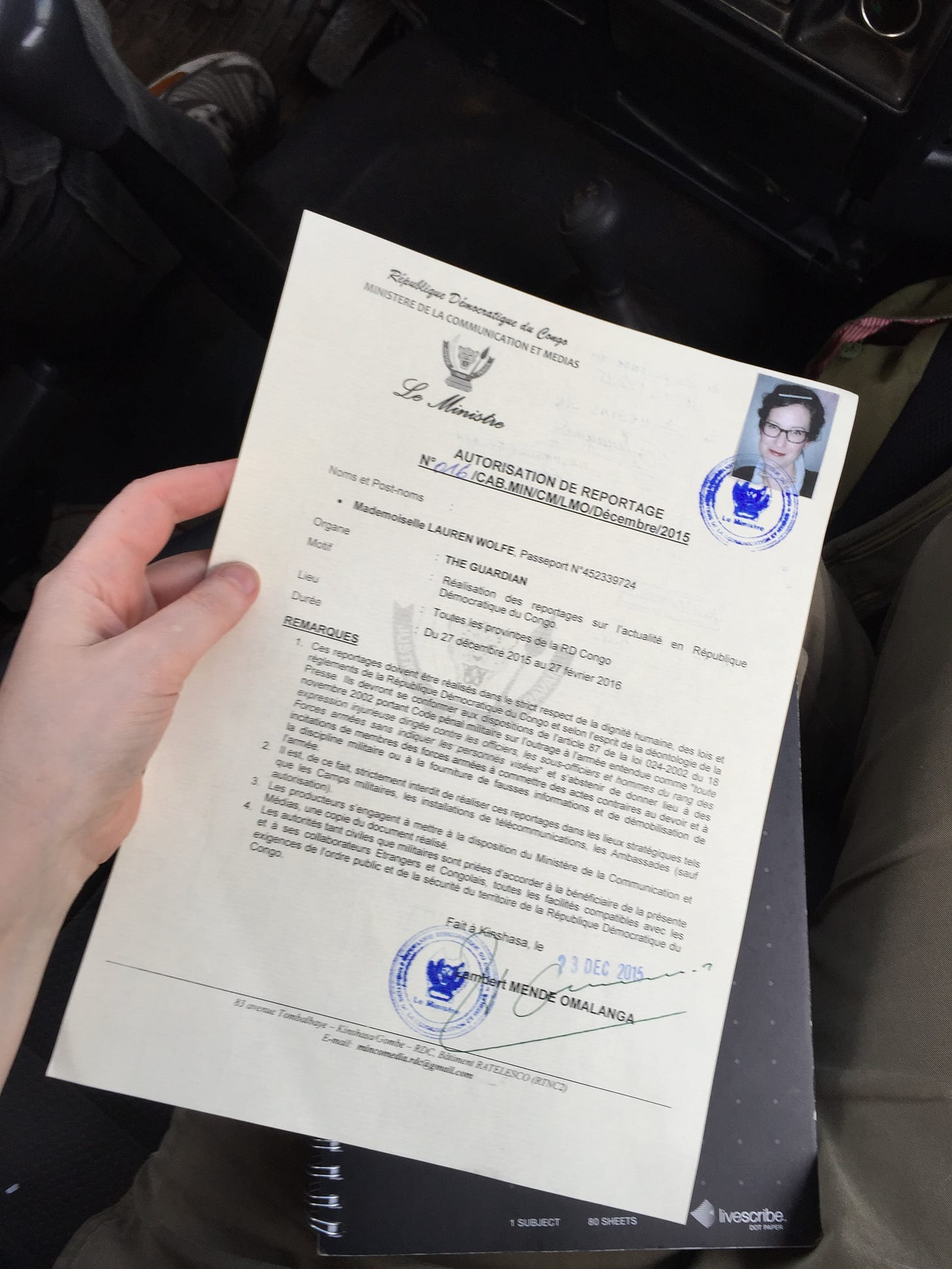

My fixer, whom I’ll call Jack (since he is known to many as “Jack Ryan” because of his multiple impressive field skills and bravery), was handing over official papers, one by one, that I had procured before leaving New York: a letter of support from a “host” organization, a letter from a media outlet explaining that I was in the country working for them (in this case, The Guardian), copies of my passport, my visa, proof of what hotel I was staying at, and probably five more things I am forgetting now. There could have been only a single piece of paper for this man to review though, and I still believe we would have sat there melting for the same hour or two we did as he scrutinized each word, slowly and repeatedly.

(See: small-time officials trying to seem important.)

It was December 2015. It had been nearly a year since my first trip to DRC, and I was back, this time specifically to investigate the rapes of dozens of little girls in a village called Kavumu, in South Kivu province. (For those of you new to this behind-the-scenes series, I’d suggest reading Part 1 before this.)

Dozens of girls (aged 18 months to 11 years old) had been kidnapped from their homes in the middle of the night, taken to a nearby field where demobilized soldiers were squatting, and gang raped and left bleeding under the stars, alone. Over the course of nearly three years, not one arrest had been made that actually made any sense, and everyone was too frightened to look too closely at who might be carrying out the attacks. For good reason.

Preparation for a reporting trip like this is…intense. The sheer number of pieces of equipment you need to pack feels endless (camera, lenses, batteries, chargers, cables, computer, Livescribe pen — which is magic; get one if you are a journalist or work in the field somehow — many notebooks, pens, SD cards, backup tape recorder, pro-microphones…), as well as the shoes needed for muddy climbs, clothing for hot but rainy-season weather, malaria pills, any other medicines you need, one nice outfit, and on and on.

Then there was the succession of shots I had to get very quickly in New York: Yellow Fever, Hepatitis A and B, Tetanus, Typhoid and I don’t remember what else. All I know is that one of them felt like a tiny snake was being inserted into my arm.

Most of all, you have to make sure all your papers — including your much-valued media accreditation — are in order because authorities in DRC, as in many unstable places, like to have a pretense to shut reporters down, and it doesn’t take much. (After I’d taken this trip, a number of researchers and reporters were allowed to land in Kinshasa or Goma or other Congolese airports only to then be kicked out.)

Before I left New York, I diligently gathered everything. But here, in this smothering hut, all that effort was reduced to a single stamp on a single one of my papers. This was just the first of many stamps we needed to gather on a dizzying circuit of visits to Congolese offices. And the stamps have to be obtained in the correct order or you can be booted out of the country, or arrested (which I soon was. Getting to that).

Oh, I nearly forgot: You know how I said in Part 1 that this trip would be expensive? I want to explain that this meant I had to carry thousands of dollars on me — in cash. The hotel, my fixer (who in this case was doing double duty as my translator in Swahili/French/English) and my driver would only take cash, and it’s not simple to pull money from your U.S. bank without hefty fees.

But that’s all a lot of boring logistical stuff. The truth is, I had gone, alone, to a place that the U.S. government specifically tells you to not go. Right now, on the State Department’s website is this detailed warning:

Do Not Travel To:

North Kivu province due to crime, civil unrest, terrorism, Ebola, armed conflict, and kidnapping.

Ituri province due to crime, civil unrest, terrorism, armed conflict, and kidnapping.

The eastern DRC region and the three Kasai provinces (Kasai, Kasai-Oriental, Kasai-Central) due to crime, civil unrest, armed conflict and kidnapping.

A trip like this is a calculated risk. Before I left, I did my due diligence, speaking to experts who live and work in DRC as well as Congolese friends who have a good grasp of the security situation at any given time. At that point, South Kivu was considered relatively safe, with armed militias only making occasional incursions into the province. Although things were heating up in the streets as the 2016 presidential election approached — then-President Joseph Kabila was clinging to office after his technically final second term — Bukavu, the base city I’d be staying in, was considered to be at a decent state of rest.

I wrote up a security plan that included my flight and hotel information as well as all possible contacts and phone numbers for relevant embassies, friends and places I knew I planned to visit.

Having worked at the Committee to Protect Journalists for years, I knew how important a document like this could be. But young journalists: Beware. No editor is likely to ask you for such a thing. Make one anyway. Give it to her and to your close friends and relatives. Overprepare.

As much groundwork and due diligence as I did, however, the truth of it was — if I can finally be honest with myself — I was walking straight into a war zone where a bunch of madmen were raping little girls.

For years they’d gotten away with it, and I’m pretty sure they intended to continue getting away with it, whoever they were (a militia? The government? A lone monster and his monster cohorts?).

And these were people who had no problem killing Western journalists and aid workers, as the murder of two UN investigators in 2017 would soon prove. A couple years after that, I would learn that one of the investigators, Zaida Catalán, had written my name on a page in her notebook. She too had been following what was going on in Kavumu, and, apparently, she had planned to get in touch. I wish badly that she had.

Before I leave off until Part 3 of this series, just a few reminders of why I am telling you all these details:

A month or so after I left Congo, a local human rights activist named Evariste Kasali who had tried to speak out against the attacks was shot dead in his own home while eating dinner with his wife and nine children.

Rumors that sorcery was somehow connected to the rapes were flying — how else would houses packed with as many as 13 family members not wake up as men broke in and stole their little girls if there was not some magic powder being sprinkled over the structures? Congo is a place with a heavy belief in witchcraft. Combine that with a never-ending war and a traumatized population, and the mix is combustible.

Eastern Congo has long been haunted by bogeymen who rape women and murder innocents. There was just no way to know who, on my arrival, was lurking in the tangles of jungle or urban tumult and, in this deadly story, when they might strike.

And, while it was too dangerous for anyone local to look too closely into who was organizing these attacks, within three days, with the slightly better protection of someone who would soon leave the country, I had my eye on a particular man — who turned out to be a member of government. This is why it was so critical that I — a foreigner with a level of protection that local journalists do not have — still take every one of the precautions I’m talking about.

I would quickly discover that I did, in fact, have our man.

Coming in Part 3: The next, and most frightening, stop on the circuit to get my papers stamped and approved. Wild guess how that goes? I’ll describe what it was like to be detained by Congo’s big-time intelligence service for a day in a stifling-hot office that was so poor there were no phones, and one of the men “guarding” me hadn’t been paid in six months. Picture holes in walls stuffed with crumpled papers for a filing system and couches so sunken you may as well have been sitting on the floor. And, meanwhile, there is a man in the office who will not stop shouting at you.

As always, thank you for reading.

The incredible depth of detail and description you go into with this reveal makes this riveting to read.

Wow! I can’t wait for part 3!