Will Putin stand trial for the ultimate crime?

A look at how the Nuremberg trials tackled such evil, and what is possible today.

Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

In a stentorian Transatlantic accent, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson commenced the Nuremberg trials of 1945. “The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility,” Jackson said. “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated.”

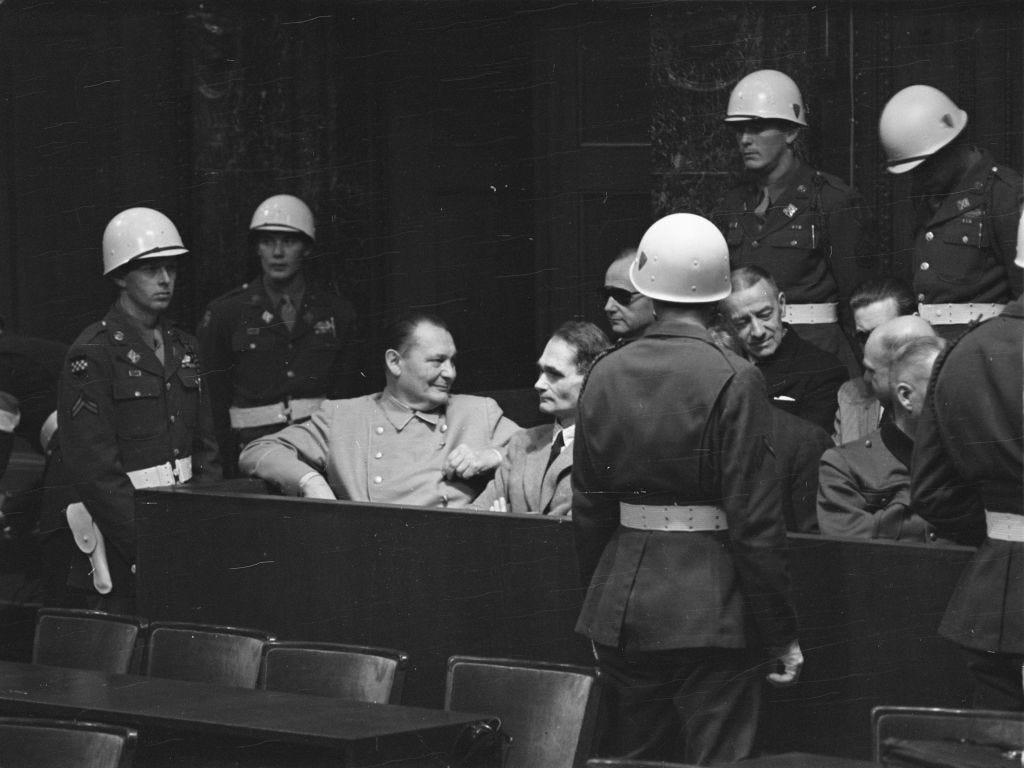

The court’s gallery was filled with a sea of (mainly) men—defendants, lawyers, witnesses—wearing clunky headphones for simultaneous translations into English, Russian, German, and French, as well as dozens of white-helmeted guards. Jackson, the United States’s chief prosecutor of Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, told the courtroom that he intended to “utilize international law to meet the greatest menace of our times—aggressive war.”

While aggression may have been “the greatest menace” at the time of the post-war trials of Nazis, it was not until 2010 that the crime of aggression was added to the “core crimes” prosecuted by the International Criminal Court at The Hague. (The other core crimes are genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.) A charge of aggression means going after the top leaders who ordered the atrocities. Because “almost every case of aggression results in the commission of other international crimes,” the Nuremberg tribunal called aggression “the supreme international crime, differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.”

Beyond Jackson’s Nuremberg declaration about aggression being “the greatest menace of our times,” Matthew Gillett, a lecturer at the law school of the University of Essex in the U.K., argued in 2013 that the Justice’s words are trumped by the court’s declaration that “crimes are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced”—thereby positioning aggression as a crime of individual responsibility, not necessarily just a matter of war between states.

So when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky unexpectedly popped up at The Hague on May 4, he chose his words deliberately: “Impunity is the key that opens the door to aggression,” the wartime leader said. “If you look at any war, any war of aggression in history, they all have one thing in common: The perpetrators of the war didn’t believe they would have to stand to answer for what they did.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Chills, by Lauren Wolfe to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.