Why Israel Bumped Ukraine Off the News

How much time and energy can we spend on giving a crap before we block a story out?

Fearless reporting, a behind-the-curtains look at how journalism is made — and an unabashed point of view. Welcome to Chills.

As the initial shock of Hamas’s attack on Israel wore down and the horrifying campaign against Gaza began, I began to think about how there is little that could have knocked the war in Ukraine off the front pages other than something involving Israel. Or a terror attack in America.

As a reporter who has covered Ukraine since the war began in February 2022, I, like many of us, have been dealing with a kind of complex pain since the Hamas attack on Israel, which was horrific and was followed by utter brutality upon innocent Gazans. As I’ve written, I was traveling to a journalism symposium at Auschwitz when the initial invasion occurred. That was really a kind of F-U from the universe if there ever was one, right?

I took a look at Google Trends to chart the progress of global news searches about these two conflicts. You can see spikes of searches for “Ukraine” on Google News on Feb. 24, the day Russia invaded, and on Oct. 7 for “Israel,” the day Hamas attacked Israel. Nothing surprising there.

Key:

Blue=Ukraine

Green=Russia

Red=Israel

Yellow=Gaza

According to Google, points on their graphs reveal numbers that reflect how many searches have been done for the particular term relative to the total number of searches done on the site. More from Google: “Numbers on the graph don’t represent absolute search volume numbers, because the data is normalized and presented on a scale from 0–100, where each point on the graph is divided by the highest point, or 100. The numbers next to the search terms at the top of the graph are summaries, or totals.”

These numbers encompass searches in news worldwide.

So if you look at the week of Oct. 8-14, 2023, you can see that Israel hit a peak. What I find interesting is that news searches for “Gaza” in the same period barely made a dent. I assume this is because Israel had not yet begun its deadly campaign against the territory. Israel had the maximum of 100 searches the day after the Hamas attack. Searches within Google News show that stories about Ukraine hit a peak on the day of the Russian attack, Feb. 24, and fell off precipitously after that. There’s nothing surprising about this. Holding readers’ attention on a painful story is notoriously difficult.

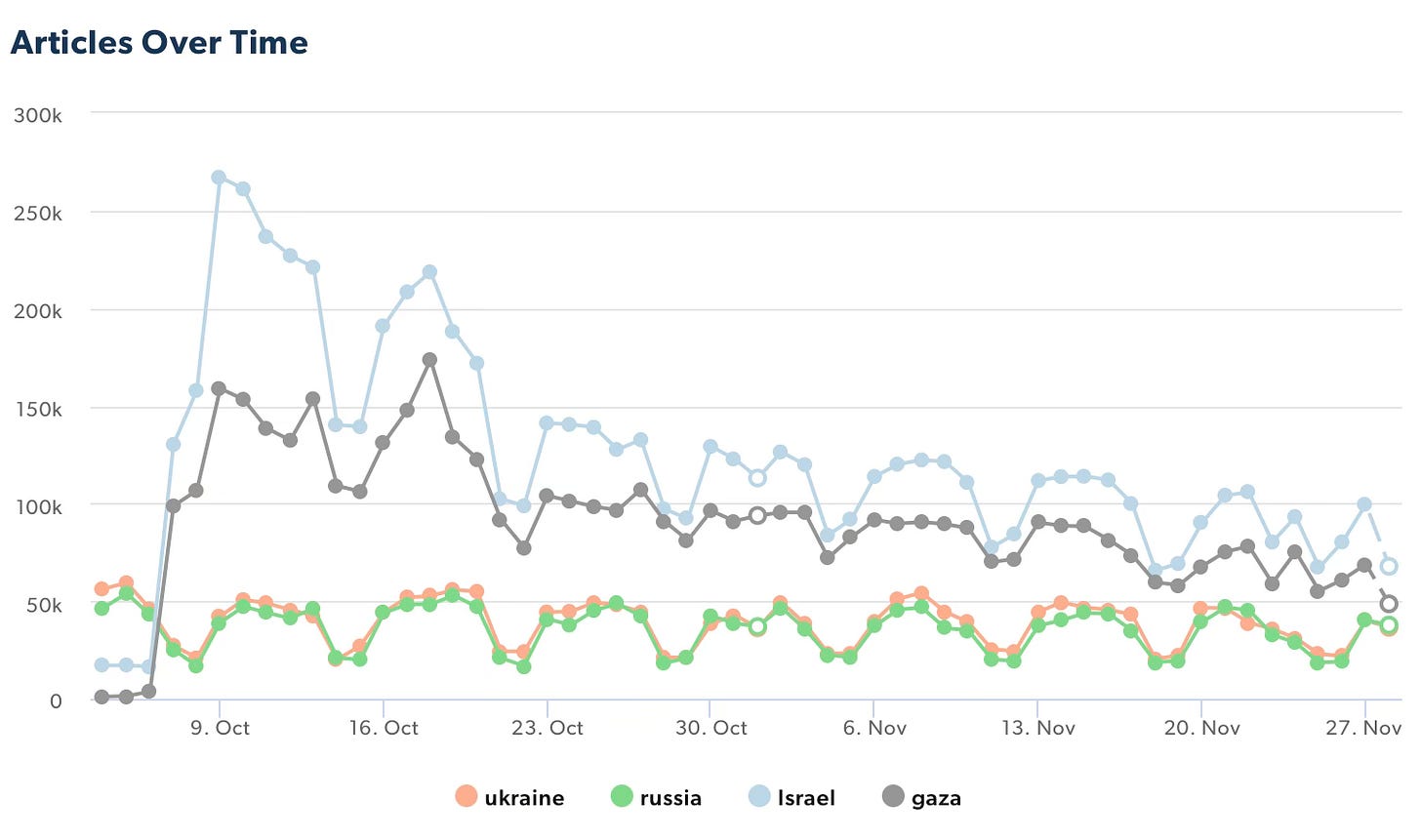

Separately, I used Muck Rack’s trend tool to track mentions of these places in the news media since October 2022, which looks like this:

I find this tool confusing, however, as the numbers include press releases and aggregated news results. So, grain of salt.

As journalists, we are somewhat enslaved by the attention economy. It’s not as blatant as many seem to think, however. I’ve never once in two-plus decades of experience at multiple national news outlets ever been told by an ad person (or editor) to tone something down or to back off a particular story because of ad sales. Yet it’s impossible to deny that editors are under pressure to publish stories that bring clicks, which brings ad revenue, if only to keep their jobs — and hopefully get a raise for their mainly garbage-level salaries.

With the agonizing, prolonged death of the news industry, many of us in the media have internalized this kind of story selection to some degree. I think the key is to recognize it and proceed accordingly. Aka don’t sacrifice important stories, but also consider that nobody will have a job if you don’t do certain kinds of “fluff” or “controversial” stories.

I’ve written a lot about what I think of as “the economy of caring” over the years. Such an economy is as potent as the financial one, or more so. How much time and energy can we spend on giving a crap before we block a story out? What is the breaking point? This has a lot to do with what gets published and doesn’t, and people’s capacity to ingest horrors. And they are intertwined with media outlets trying to get enough readers to stay financially afloat.

In 2014, I wrote about the difficulties of sustaining attention through the press. I spoke to feminist activist and writer Gloria Steinem about what grabs readers. To start, I asked in this piece for Foreign Policy, what makes a cause or campaign, when it bursts onto the scene, really take hold? This was during the kidnapping of hundreds of schoolgirls in Nigeria by the terrorist group Boko Haram. A global campaign took off to free the girls, called “Bring Back Our Girls.”

Steinem’s response: “‘Bring Back Our Girls’ was the function of not only a story that created empathy, plus the Internet, but an unfinished story, so our minds kept pushing at it, as if at a sore tooth.”

In other words, I wrote, it’s the lack of a resolution — and the potential of one coming — that grabs interest. But Steinem said, too, that she fears people lose interest in staying until the end when it doesn’t come quickly enough. People are in it for the plot, and they’ll turn their attention elsewhere when the twists stop happening. That fits with the media’s treatment of the war in Ukraine, as well as the capacity for public attention. While the war maybe would have stayed front-page news longer if Hamas had not invaded Israel, the news about Russia’s incursion was way down in any case.

In the era of TikTok, the overall attention economy is perhaps the barometer we need to pay more attention to if we want to continue to enjoy a free and robust media.

So what are we in the press supposed to do?

“It’s been my experience that the single most important bridge to caring is not a fact or a statistic, it’s a story,” Steinem told me.

Sounds good, and it’s how many of us introduce painful stories to the public, but have readers become immune to such depictions?

Remember the “Portraits in Grief” published by The New York Times after Sept. 11? They were groundbreaking. Creating a (relatively) full picture of each person who tragically died in the attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon was a new kind of very personal journalism. (Aside, I had the privilege of being a reporter/researcher on 102 Minutes, an account of the final moments of 9/11 victims by New York Times reporters Jim Dwyer and Eric Lipton. I highly recommend the read, which was a National Book Award finalist.)

Despite the pathos in those small portraits, In the years since, I’ve heard endless grumbling (although maybe mostly in my own head) about how now every tragedy gets this treatment — we see these more intricate portraits of victims so often — victims of every mass shooting, etc. — that we’ve stopped seeing them.

Still, there is reason to persist.

“We have to identify in order to care,” Frank Ochberg, a psychiatrist at Michigan State University and chairman emeritus of Columbia Journalism School’s Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, told me. “We can’t just satisfy our curiosity; we need more than that. The human portraits have to evoke evolving emotion. If we just feel outrage or pity or even compassion, that isn’t enough. We need to go through the stages that draw us into life narratives, sustaining our attention, our belief that some significant denouement is on the horizon.”

On Oct. 7, the day of the Hamas assault, and Oct. 8, the day after, searches for “Gaza” were at 0 on Google’s relative scale. The number of news articles, according to Muck Rack’s seemingly problematic search tool, put the peak of mentions on Oct. 9, on which 267,000 articles discussed “Israel” and 159,000 talked about “Gaza.” (“Ukraine” and “Russia” hovered at around 50,000 articles each.)

If we’re going to relate to what’s going on in this terrible war between Israel and Hamas, then we have to start looking. If we want to understand the biggest war in Europe since World War II, we have to start reading. And right now, the press isn’t helping.

Fortunately, we’re not a monolith. The media is composed of the best and the worst of us. People who are fallible and who may or may not be over-weighting coverage of one thing or another, but also people who are watching for just such an imbalance.

One caveat: It’s also up to the readers to seek out news about all sides from reputable news outlets. Unfortunately, for many news consumers, these days, that has become a Sisyphean task.

Chills is self-funded, without ads. If you want to be a part of this effort, of revealing how difficult reporting is made — of sending me to places like Ukraine to report for you — I hope you will consider subscribing for $50/year or $7/month.

The Israel/Hamas war even threw Trump off the news. All a gift to Putin.

You brought up the Nigerian girls. I’m old enough to remember the Iran hostage crisis. We were glued for literally years to that story. But news and the media were so different then.maybe we were too.

Maybe you should visit affected communities in Southern Israel before you are so quick to judge Israel's response, or at least view the 45-min horror film of Hamas' extreme brutality, like many respectful journalists have done (such as Douglas Murray)