Fearless reporting, a behind-the-curtains look at how journalism is made — and an unabashed point of view. Welcome to Chills.

They’re cutting and running. That’s what we’ve been hearing for a while now about Russian troops in Ukraine — they’ve been retreating so frantically that they’re changing into civilian clothes, dropping their weapons and fleeing.

Because of these hasty and ill-planned retreats, unlike in previous conflicts, such as Rwanda or Bosnia, the war-trod ground of Ukraine offers a unique opportunity to investigate crimes nearly as they happen. Once Russian troops have pulled out of an area like the suburbs northwest of Kyiv — killing grounds such as Bucha, Irpin or Hostomel — investigators are able to rush in and scoop up information that is still fresh. Recollections are still reliable (mostly), and physical evidence like unexploded ordnance or bomb fragments can be gathered. Documents left by fleeing Russians can be collected and preserved. And, unlike in a place such as Syria, once the enemy has pulled out, it’s unlikely they’re coming back.

Side note: Speaking of fleeing quickly, I was told by a solid source that Ukrainians have set mines in (now formerly) Russian-occupied areas, but because Ukrainian forces may have had to change locations so quickly, they never left maps of where exactly the explosives were. I drove past at least one otherwise empty field in which people wearing extreme body armor were carefully combing for them.

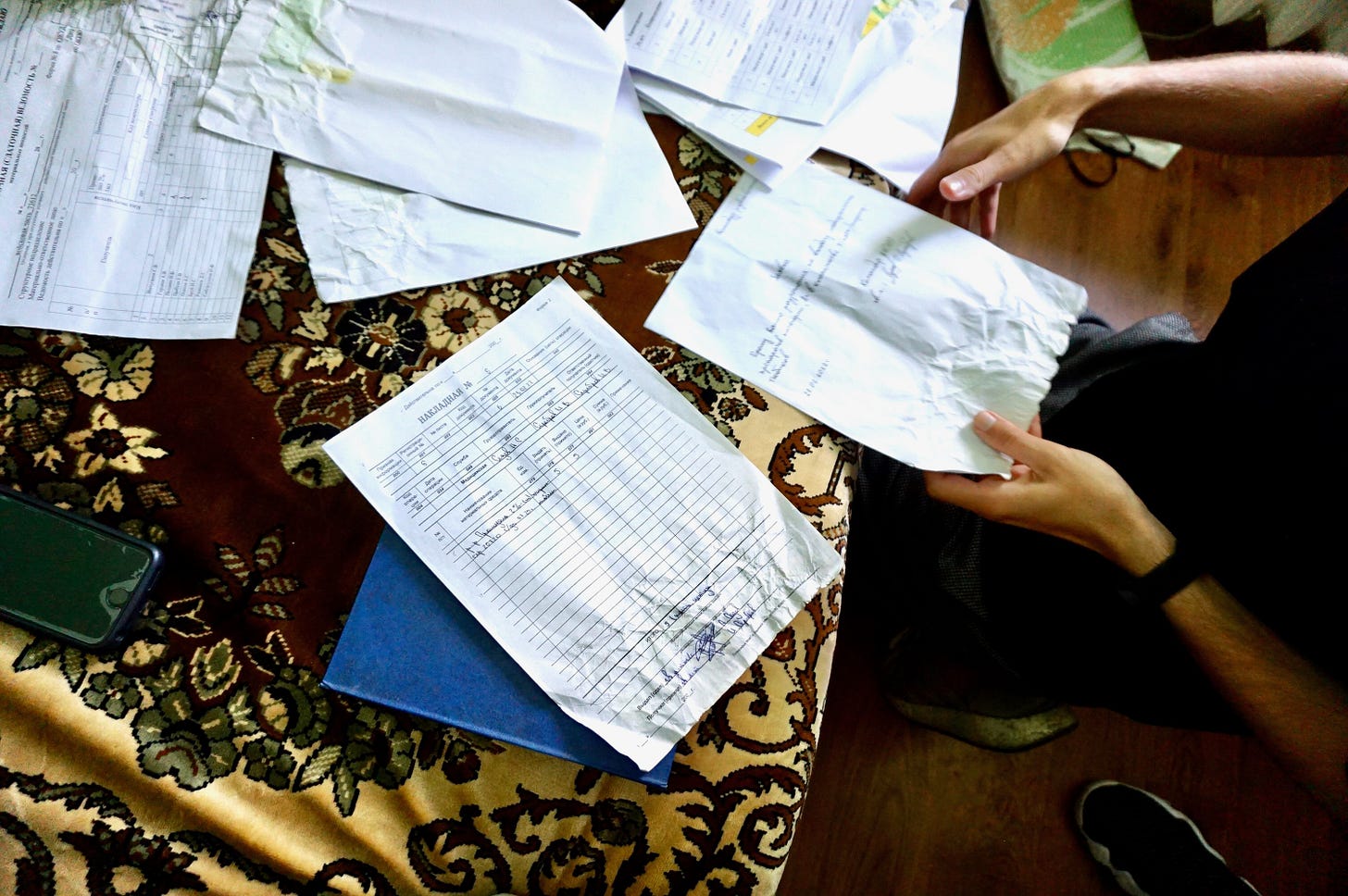

As a result of all the frontline havoc (or perhaps out of simple carelessness), bags and bags of Russian documents are being left behind in people’s houses, churches, airports, etc.

“The more organized the military, the more documentation there is,” one experienced war crimes investigator told me. “It takes a lot of work to put on a military operation. Everything has to be inventoried, moved, etc. It’s life or death.”

And while Russian soldiers have proven to be far from the mighty, well-equipped minions of Ares the world once believed them to be, they have documented a ton of what they’re doing in Ukraine — in a Soviet-style, the FSB-is-watching-us, Cold War kind of way. And luckily for those who are pursuing justice for Russian crimes, the fecklessness and/or haste of the Russians has given Ukrainians and international investigators a trove of papers to use.

Having been handed a cache of Russian documents while in Ukraine over the summer, I’ve been learning a lot about what needs to be done to make the papers viable evidence in court.

Here are some of the ways found documents can end up as critical evidence in a war crimes trial:

First, though, what makes for a powerful piece of documentation?

The most compelling finds are very specific, international war crimes investigators I’ve spoken to say. These files corroborate witness statements, video and photographic evidence, and things like cell phone records. You want to be able to show a command structure, or pages that notate who is in charge of what — even something as small as the requisition of fuel or ammunition can indicate this. The questions investigators ask include: How does the command structure work? Who are the subordinates and who are the commanders? Something as simple as a purchase order (I have requisition forms for a heavy anesthetic left by the Russians) can show that a substantial structure is in place — in which one person needs to obey another person or unit.

Some historical context: Found documents helped convict Bosnian Serbs for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

During and after the Bosnian war, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia obtained documents through search and seizure in various places, such as police stations. A search of Gen. Ratko Mladić’s attic recovered wartime diaries that were later used in the ultimately successful case against him. The Bosnian Serbs’ hoarding of documents such as fuel receipts, notes on the movements of excavation equipment and work logs showed that such papers can lead to when, where and by whom executions were committed — these guys tended to save everything. And, as one expert told me, war criminals may hide certain papers, but they don’t always know what to conceal. Seemingly meaningless documents like fuel receipts or work logs can be extremely valuable in reconstructing events.

More context: The Nazis’ own documents incriminated them.

Similarly to the ICTY, prosecutors at the World War II International Military Tribunal were able to use the Germans’ own words — as well as nightmarish film taken by soldiers who liberated concentration camps — to convict them. The lawyers’ efforts eventually led to the trial of members of the Nazi regime in Nuremberg. Judges from Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the United States tried 22 Germans on charges of conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity. In 12 later proceedings, the United States tried an additional 183 German leaders.

Importantly, the WWII prosecutors did not rely on personal testimony that might be viewed as biased. The cases relied primarily on thousands of documents written by the Germans themselves. There were 19 investigative teams assigned to gather and investigate hundreds of thousands of German records.

Many of the Nazi documents and some of the historical records were destroyed at the end of the war during a mass paper purge, and in the Allied bombings of German cities. However, notably, the allies gathered German documents known as the Einsatzgruppen Reports (the Einsatzgruppen were mobile killing units that committed mass shootings; one unit murdered more than 33,000 Jews in two days at a ravine known as Babyn Yar, in Kyiv). These were actual records of Nazi policies and actions. Used at Nuremberg, they were critical to proving that the Holocaust had really happened.

Then there was the Wannsee Conference Protocol — one of the most important surviving German documents on the Holocaust. It comprises a revised version of the minutes at the Wannsee Conference (Jan. 20, 1942), where the Nazis devised a plan to use their murder machine to kill millions of European Jews. The document lays out the top Nazis’ agreement to collaborate on a continental scale in the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” Or, in other words, mass murder.

How to prove a document is authentic.

As I wrote in my recent Guardian piece about all this, you can have all the bags of found documents you want, but proving that they are the real thing — and not something concocted by a prosecutor — is a different story. Here’s what I’ve learned from experienced investigators about how to authenticate docs:

Compare your document with other ones you know are authentic. Check for the same format, stamps used, who it’s addressed to, reference numbers, etc.

Show the provenance of the document; i.e. where you got it from, and who had it before them — just like a work of art. What has been the chain of custody, as with any evidence presented in any courtroom.

Another way to help prove authenticity is to have experts — maybe from the military — testify.

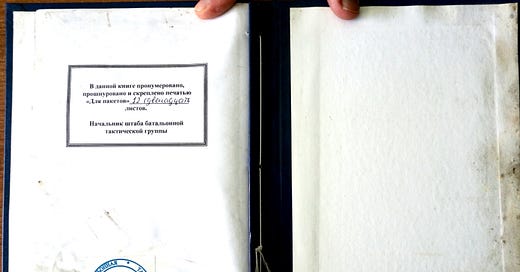

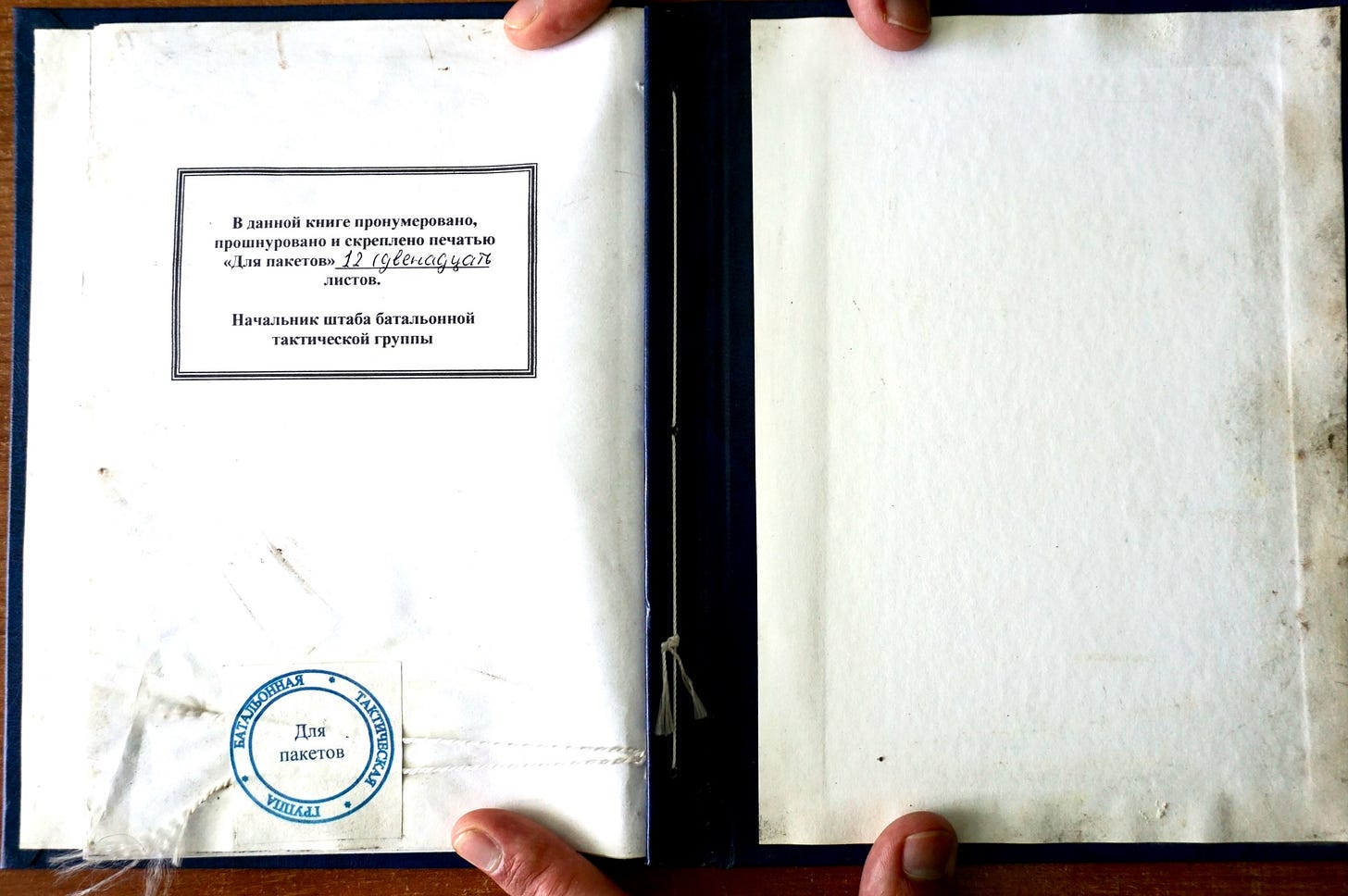

In the case of a hardback Russian book I was given that was found at Antonov Airport, in Hostomel, there was an unbroken seal, which certainly helps in proving it has not been messed with.

A high-tech spin on how to use found documents.

Research organizations like the Center for Information Resilience and Bellingcat employ highly technical mapping and databases. They also use CCTV footage and, in the case of Ukraine, radio intercepts they’ve been given by the Ukrainian government. All of these puzzle pieces can be used to identify houses in which people were held as well as convoy routes, which can then lead to a further conclusion: Pierre Vaux, a CIR investigator, told me that “where there were Russian convoy routes, there were often killings of civilians along those routes.”

It may also be possible to pinpoint the houses of Ukrainian collaborators by following the Russians’ movements. Really, the possibilities are endless. I’m far from done in working with the documents brave Ukrainians gathered up and handed to me. I will continue to endeavor to find out what can be gleaned from the pile of Russian papers I was shown, and update you as I can.

I need your help to keep doing the kind of unique journalism that is Chills. You can help this newsletter expand its content by subscribing. I tell complicated stories from dangerous places — and I do my best to do so ethically.

Chills is self-funded, without ads. If you want to be a part of this effort, of revealing how difficult reporting is made — of sending me to places like Ukraine to report for you — I hope you will consider subscribing for $50/year or $7/month.

This most recent article reminds me of the January 6 hearings where the evidence was provided by witnesses from within the administration, their texts, etc. perpetrators of evil leave chunks of bread rather than breadcrumbs to guide the way. But while fuel receipts and schedules can place personnel, the rapes and murders will be harder to prove. I’d be interested to know what evidence is used to prove those crimes.

I hope you (and your readers) will be able to learn how the documents you were given help in obtaining justice for the people of Ukraine. And soon.