Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

Instead of writing a remembrance today, I’m re-upping this essay. It encapsulates what this day means to me. Sending love and safety to all.

The darkness had a gritty quality to it. You could hold it in your hand, rub it between your fingers. Ghostly paint on the sides of buildings spelled out names of enigmatic businesses long gone; one wispy sign read “Brush Up Business With Paint, Paste, Paper, Push.”

It was 1997, Tribeca. The building I was heading into vibrated with stereo bass, and I felt an excited shudder laced with anticipation in my gut. This was my first real adult “New York” party — the kind where strangers danced with one other and strange things happened in bathrooms.

The city was dirty and graffitied then. Crime had fallen under Mayor Giuliani’s reign, but murders and violent crimes were still twice as high as they are now.

Life felt scary but expansive that night. Scary in its expansiveness. The very grime that kept so many people away from the city fed the rest of us with possibility. Of what, we weren’t sure. But that was it: We craved the unknown. We were young, we were alive, we had wonder in our souls.

I have no memory of the actual party that night — my mind is stuck in the dank doorway that leads to a stairwell with a single bare bulb. After this, the rest of my recall turns the night into a blurry outline of Scorsese’s “After Hours”: adventure, folly, bizarre people and an undercurrent of danger, as if, like Griffin Dunne in the movie, I spent an endless night trying to find my way home.

And, eventually, the trip became exhausting.

I left New York a couple months ago. I think for good. It may be where I’m from, but I no longer had much love for its gray streets. They’d long ago given up their mysteries — or I just stopped caring about solving them. The city had become a supporting character in my lifelong gray depression.

So this was one of the only years I’ve not been in New York for Sept. 11. I still can’t look at photos of the towers, and I still startle at planes and sirens. The attack is part of my soul as a New Yorker, but this year, I didn’t immediately think about my 9/11 story, as harrowing as it is.

What hit me instead was the time before that explosive, blue-skied Tuesday. For some reason, on the 20th anniversary of that day, my mind went back to that Tribeca party. I’ve been trying to figure out why.

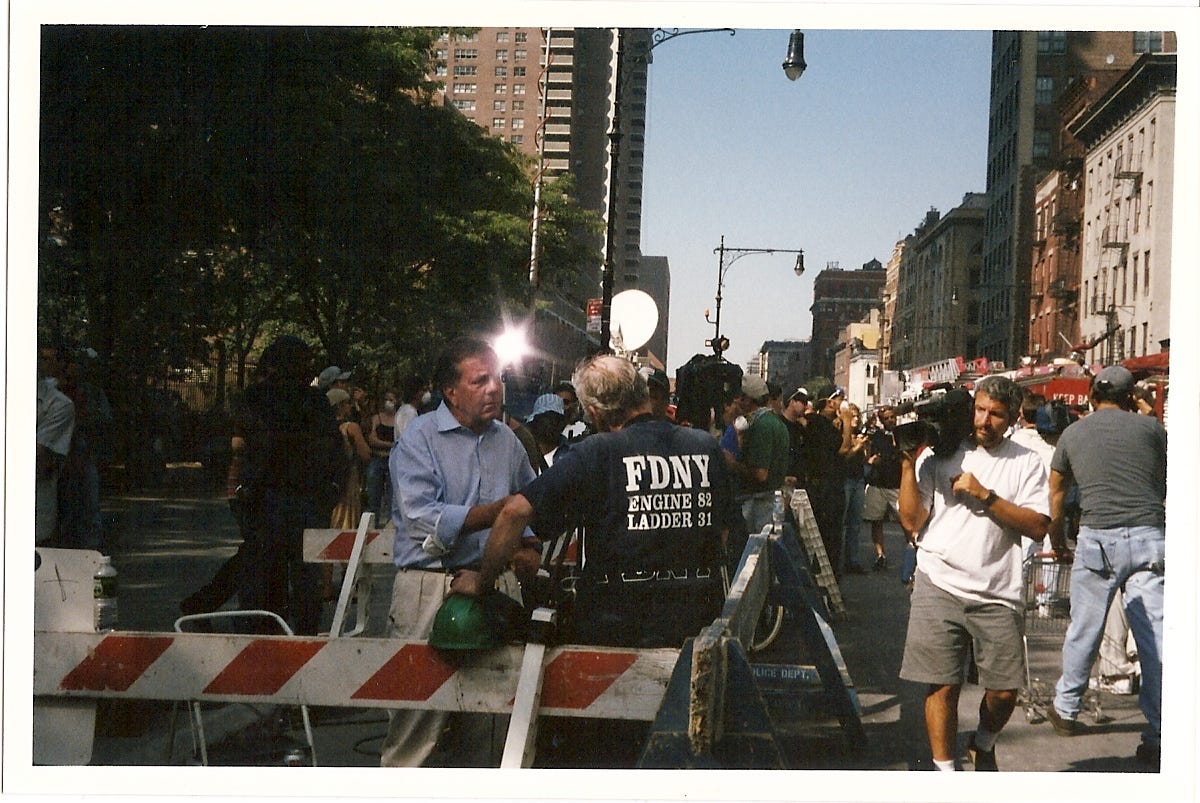

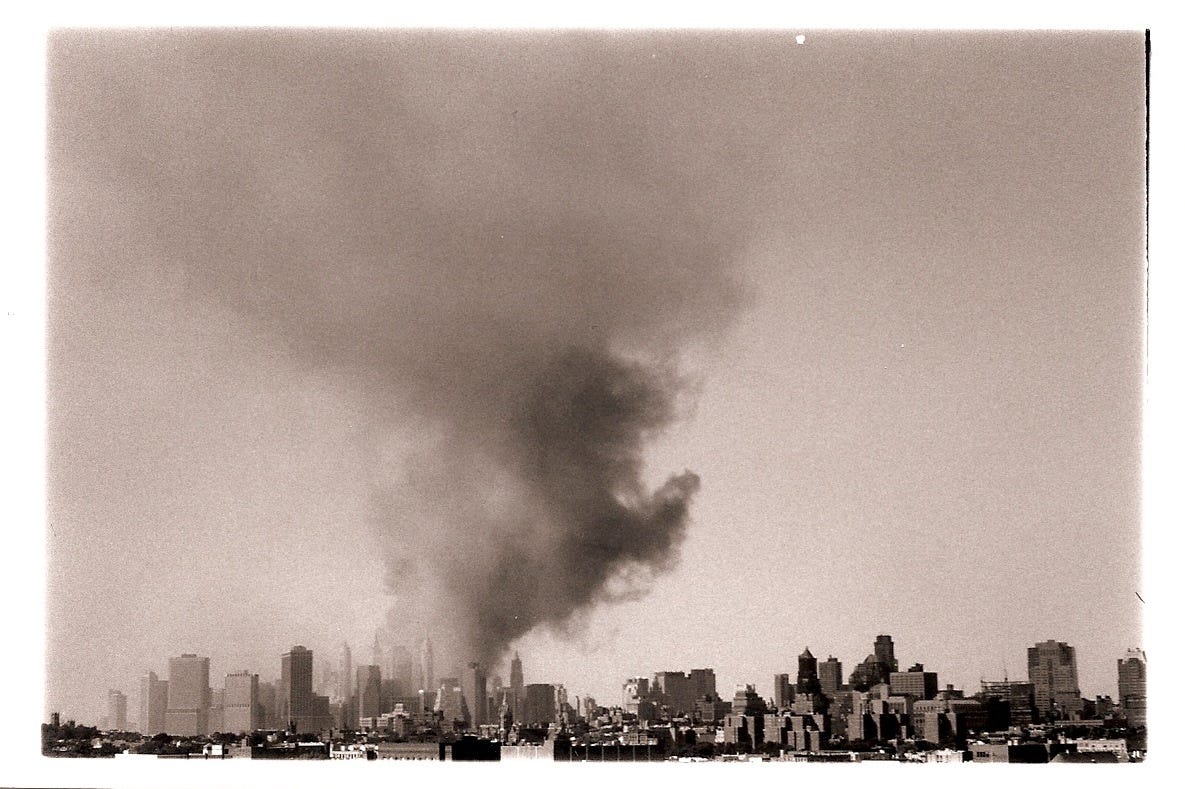

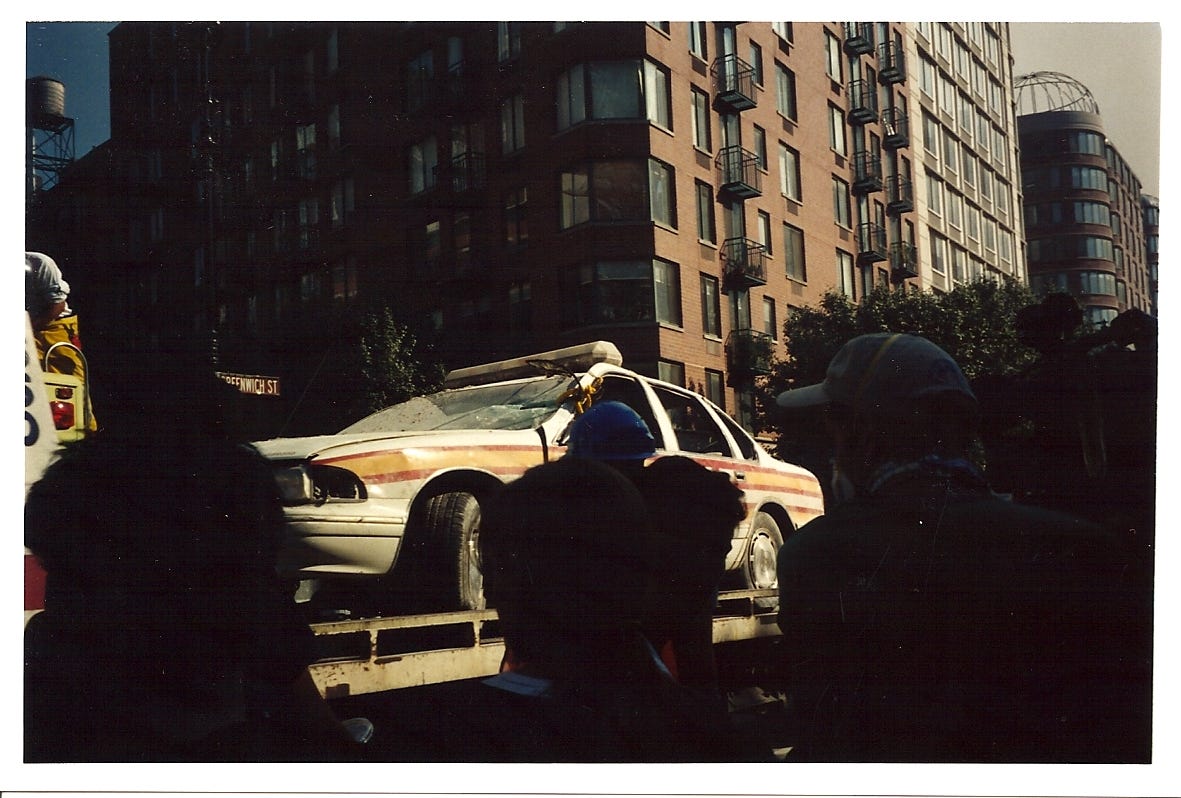

Last week, I tweeted a few photos I’d taken at Ground Zero on Sept. 13, 2001. I’d been using both color and black-and-white film that day and had to stop on Greenwich Street to buy more. I tweeted that too. I wasn’t sure why these details seemed meaningful until I realized that many people on Twitter have never even used a film camera. I found myself explaining camera basics.

I’d just started at Columbia Journalism School in May 2001. On the day I spent at the pile, I ran into a New York Times reporter who’d spoken to my class. Everyone downtown was devastated, breathing in soot and sublimated bodies, wandering between crushed cars, military Humvees and clergymen. I was interviewing people and taking photos, but I felt useless. I didn’t work for a news outlet. I didn’t know why I was there. I just felt like I had to be.

I told the reporter that I had class in an hour and that I wasn’t sure whether to stay downtown or go to Columbia. He told me that I was doing everything exactly right, but that, in no uncertain terms, I had to get to class.

“We need the next generation of journalists,” he said. And it was my duty to learn.

One of the only things I remember from that semester is the shocked look on my professors’ faces as they grappled with the fact that, as they put it, journalism had just changed forever.

I wasn’t sure exactly what they meant at the time, but in retrospect, it seems clear. Terror would become our new normal. Covering it would require new skills and geopolitical understanding, just as living in our changed world meant learning to adapt to a new kind of fear. The internet was ascending — minute-by-minute updates were becoming easier to do.

That time is a chunk of in amber in my mind, but in actuality it was just the beginning of the rest of my life.

Still, that party. Why did this year’s anniversary of Sept. 11 trigger that memory?

Back then, just out of college, my friends and I had no concept of a life so frightened. A combination of being young and adventurous made me feel that anything was possible, that existence itself was an exhilarating unknown. Or, at least, that it was possible to find exhilaration between the bleak times.

We all aged a fair amount in those months. The violence of Sept. 11 and the loss of friends and family was a hard kick into adulthood. For me, it also coincided with and fed a newfound need to report, to record history as it happens.

But while I can still smell the chemical, ashy air of 2001, the years since it happened have melted into decades. Time really does move faster as you age.

This year’s week of Sept. 11 brought its own tragedy: My tenant in my New York City apartment died of a sudden aneurysm. She was 39. My father’s friend, 78, was killed when floodwaters subsumed her car during the storms in the Northeast that followed Hurricane Ida.

At the same time, my father drove across the country to a city he’s never been to and moved into a place near me. He’s 80 years old, and arrived exhausted in both body and mind. Finding one’s way home is exhausting.

These factors have coalesced to make me feel my fragility as a human. The passage of time, how tenuous the amount we get is — combined with PTSD from Sept. 11 . . . I guess it’s left me reflective, if not a little morose.

Sometimes I am distraught about the idea that the people I love who are gone now never got to see so many things that happened after they died. Even the bad things, awful world events like this pandemic. With my father here, I think about the many things he’s experienced in his eight decades. Events, places and even people that are fast becoming “history,” as fewer and fewer people remember them directly.

And what will happen after my father is gone that I will wish I could share with him?

That’s how I’m feeling about Sept. 11 this year. That those of us who were direct witnesses will be gone soon, and the terror inflicted on my city will be just distanced words and images — a simple historical fact, known but not felt, as interesting as how a film camera works in an age where few know the agony of trying to decide whether a photo is worthy of one of just 36 frames. Like the sense of magic that smoky party in Tribeca triggered in me, the vivid emotions the attack left us with will fade, as we do.

All that will be left one day are stories. And images. I can only hope that one day, kids will feel safe enough to feel that magic of possibility — and not spend the rest of their lives afraid of horrors that will drop from the sky.

There’s got to be a party somewhere right now at which people are safely masked, maybe dancing with strangers, and feeling the unending possibilities of life. As for me, I spent a long time feeling that I was endlessly wandering, dragging my memories from place to place, forever trying to find a home. Maybe, in this chance to spend time with my father, I’m starting to understand what it is like to have one. He’s here, with me, and I’m here, with him; maybe our home is this connection.

Time, as speedy as it is, will tell.

On Chills, there are no ads, and no outside influences because of it. This is a subscriber-supported space that gives a behind-the-scenes look at how risky investigative journalism gets made, from a journalist with 20 years of experience. Read Chills for free, or subscribe for bonus content like this. You can sign up here. Thank you for supporting independent journalism.

While my family was relatively "safe" in Michigan during 9/11, nobody felt that way. The world was upended, we were under attack and didn't know where or when the next hit would come. Sadly, I haven't felt safe since. We were around for the underwear bomber, too many mass shootings to count, and the attempted kidnapping of our governor. There is NO place "safe" and 9/11 was the beginning of my realization of that. I can't fathom what it was like to be in New York breathing in the air that contained your neighbors. My brain can't handle what you must feel.

Please keep telling the story. It matters.

Those who experienced the 9/11 trauma firsthand will not be gone soon: children who lived in the area and went to school there are facing decades of life.