The Turkey quake zone is filled with devastated Syrian refugees

A horror on top of a horror — I can only hope they are well, and alive.

Fearless reporting, a behind-the-curtains look at how journalism is made — and an unabashed point of view. Welcome to Chills.

This is not a picture of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, with damage from Monday’s shattering earthquake. Instead, this is an image from 2019 that shows the intentional destruction of the city after eight years of war by President Bashar al-Assad.

This is a photo of Aleppo after this week’s earthquake.

I post these two pictures to make an obvious point. The city had already been reduced to rubble before Monday. I post them because, for many years, Syrians have mourned Aleppo. The city was long known as a stunning cosmopolis clad in white marble — a place full of artists, writers and scholars.

Many years ago, I watched a friend up close, in real time, lose his city to the cruelty of war.

I’d flown from Istanbul to Gaziantep, Turkey, in the summer of 2013. The tiny airport was one of the more remote I’d ever been to, and I enjoyed its row of world clocks set to “New York,” “London” and so on, probably because there was also a clock in the sequence for the much more remote Gaziantep.

I’d gone to the Turkish-Syrian border with a colleague from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and a Syrian-American researcher who worked on my team at the Women’s Media Center. We’d been crowd-mapping stories about women and men who had been sexually violated during the then-two-year-old Syrian war. Gaziantep was where most of the international (and many local) NGOs that were working with Syrian refugees were based.

A strange mixture of ancient and modern, this place — I watched a man walk his donkey across a street that held glass-tower hotels. By 2019, Gaziantep had swelled by about 30 percent of its former population with refugees from the war. And it was the closest city to the epicenter of Monday’s quake.

After meeting with multiple people from nonprofits in Gaziantep working to assist Syrian refugees, my team moved west to Antakya, about 50 miles from Syria. Antakya was a beautiful city that was firmly on the ancient side of time.

One afternoon, my fixer, my colleagues and I ate lunch at an outdoor café. Picture vegetables so saturated in greens and reds, they could have easily been picked from the radioactive garden on “Gilligan’s Island.” The cheese, the bread, the yogurt…everything was fresh and saturated with earthy flavor, as Turkish food tends to be.

We sat under a crisp summer sky as we ate, and my fixer, who was from Aleppo, checked his phone. Something disturbed him. He looked up and said: “My high school. It’s gone.” Bombed to bits.

Such horrific revelations became a recurring theme of our time together — the daily destruction of his city was a miasma that darkened our work.

In the meantime, we traveled to towns along the border, close enough to Syria to know bombs were falling, even if we more felt rather than heard the explosions.

We were sitting on thin mats on the floor of a cinderblock room filled with women and girls in the border town of Reyhanli. More than 20, if I remember correctly (my notebook from this trip is lost somewhere in my piles of papers…) My male fixer made himself scarce.

Belongings hung from thin plastic grocery-store bags on the walls. Pitas, canned sauces. From the outside, the structure we were in was either half built or half falling down.

I met a newborn baby in that concrete room, and two young teen girls whose faces I can never forget. This is them. This is their uncertainty and pain.

The hardest thing about being a refugee, from what so many around the world have told me in the course of my work, is not knowing what comes next. Where will we live? What job will pay our bills? Will we have enough money to eat and buy medicines? Will we ever return home?

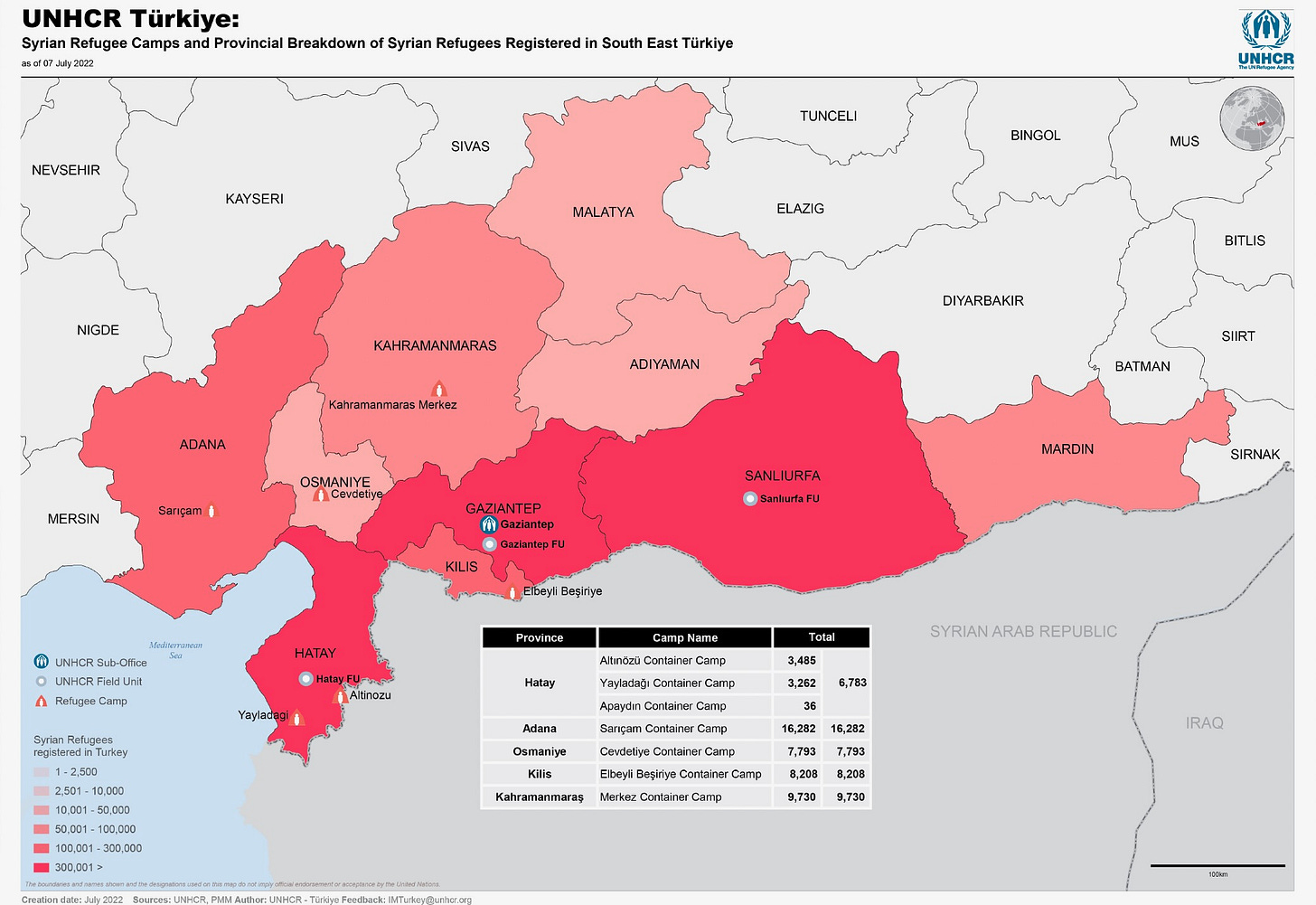

More than 3.5 million Syrians were living as refugees in Turkey as of July, according to the U.N. Refugee Agency. I don’t know about the girls or women I’ve met, what’s become of them. I can only hope they’ve found permanent homes and work and safety. And now that they were not hurt in the earthquake.

As a journalist, I generally stay in touch with sources I speak to a lot for stories. Women and girls like those I met at the Syrian border, I’ve lost to a particular moment in time; to my memories, and to the only photos I have of their sad but hopeful faces. The two girls above would be grown women now, perhaps with families of their own.

It is them I’m thinking about as images of disaster stream around the world. A horror on top of a horror — I can only hope they are well, and alive.

Chills is self-funded, without ads. If you want to be a part of this effort, of revealing how difficult reporting is made — of sending me to places like Ukraine to report for you — I hope you will consider subscribing for $50/year or $7/month.

An excellent newsletter...the scale of misery is biblical unimaginable, gut-wrenching.

So glad I receive this newsletter-and so moved by the plight of these people. Disasters may have hit them first, but we are all in this together. Who will it hit next?