The man who saved lives in the Hotel Rwanda has been convicted of terrorism (part 1 of 2)

How did he go from hero to villain?

Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

The hallway was lit with a terrible ochre light. I felt sick as I walked toward my hotel room. Inside it was another ominous sign: Half of the metal swing lock on my door had been ripped off, broken as if someone had forced their way in. Thankfully, I was spending just one night here, at the Hotel des Milles Collines — aka the Hotel Rwanda —where in 1994 more than 1,200 people survived the 100-day genocide perpetrated by Hutus against Tutsis that raged beyond the hotel gates, on the other side of which people were burned, macheted and shot to death for belonging to the Tutsi ethnic group.

“An island of fear in a sea of fire,” the then-manager of the hotel, Paul Rusesabagina once called it.

This was my second transit through Rwanda in two years, and both had been stops on my way to eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Before I’d left New York this time, I’d made the conscious choice to stay at the Milles Collines, which was once a five-star hotel, but by the time of my trip in 2015 hadn’t shaken off its association with the genocide.

During the killing, all 112 of the Milles Collines’s rooms were occupied by up to 10 people per room. Refugees also stuffed themselves into common spaces and hallways as more than 800,000 of their fellow citizens across the country were murdered within 100 days. The refugees came at the invitation of Rusesabagina, who was later lionized in the 2004 film “Hotel Rwanda.” The common story told is that he gave them all rooms for free. But a number of survivors have painted a very different picture of the man and his actions, accusing him of extorting them to pay for their shelter and food.

Rusesabagina also has made several comments over the years that turn the historical record of the genocide on its head — saying he believes that President Paul Kagame, a Tutsi (who was then the military commander of the Rwandan Patriotic Front), actually had his men infiltrate the Hutu militias. Rusesabagina has implied that, in reality, the murdering Hutus were really working for Kagame — for a Tutsi — even if they didn’t know it.

Today, Milles Collines is considered upscale, although not “the best” hotel in Kigali. When I was there at the end of 2015, I met French and Belgian flight attendants outside on the hotel restaurant’s balcony. Their laughing and drinking and chatting felt incongruous and uncomfortable, but I suppose not everyone has to take in the darkest chapters of human history during a layover.

Besides, there were no physical reminders of the slaughter in the hotel. Still, even though the walls and windows shot up with bullets and exploded with mortars had been repaired, I felt a palpable sense of desolation.

I realize that this was a dark decision. That most people don’t choose to spend the night in a place steeped in historical horror. But I’d written a lot about the repercussions of what happened in 1994, and one night would allow me to feel a tiny bit closer to understanding the acts of inhumanity — and of life-saving generosity — that had rocked Rwanda and stunned the world. One night at the hotel allowed me to feel the lingering miasma of terror and hope that permeates that place.

In 2005, President George W. Bush awarded Rusesabagina the Presidential Medal of Freedom. That same year, the University of Michigan gave him their Wallenberg Medal for his humanitarianism on behalf of the defenseless. To save all those frightened people at the hotel, Rusesabagina used his connections, bribing officials with cash and high-end commodities like liquor and cigars to keep the killers out.

But regardless of the international accolades, Rusesabagina, a Hutu (who is married to a Tutsi), was never a hero among all of his own people. In fact, he was and is reviled by the man who led the forces that stopped the killing in 1994, Paul Kagame — a Tutsi. Kagame has been the president of Rwanda since 2000, and his reputation has been mixed: He has been a darling of Western leaders, treated — and funded — as a visionary. But he’s also known for his crackdown on a once-free press and for his zero tolerance policy for dissent.

Just months after the film about Rusesabagina came out, Kagame called him a “manufactured hero.” Rusesabagina had already fled the country for Belgium by then, and in the intervening years, he became the leader (in exile) of the Rwandan Movement for Democratic Change (MRCD). The MRCD is a coalition of opposition groups, including an armed wing, the National Liberation Forces or FLN, that has carried out violent attacks. And Rusesabagina has made a few statements indicating that he supports that use of force.

Rusesabagina has also become one of Kagame’s most outspoken critics. But Kagame does not accept criticism.

In August 2020, the former hotel manager was arrested in Dubai and forcibly shipped back to Rwanda, according to his family. Another account says he was tricked into getting on a plane that he thought was bound for Burundi. Either way, his fate was secured.

Right now, the man who saved more than 1,000 desperate people by giving them shelter in his hotel is sitting behind bars, and will be for 25 years, as a result of being convicted of terrorism.

Not much is reported about Rwanda these days, like a once-dangerous dog who is ignored because he no longer bites. Rwanda is a tiny African country, devoid of overt conflict but not so far removed from its past as to be forgotten by the world at large. Since 1994, it is a country that has proven that economic, social and technological growth is possible in a very short period. Although it’s had a fair amount of assistance to do that.

International money poured into the country after the events of 1994, mostly out of what I’ve heard described as “genocide guilt.” The fact is, the world looked away during those vicious three months in 1994, even as they were being told what was happening.

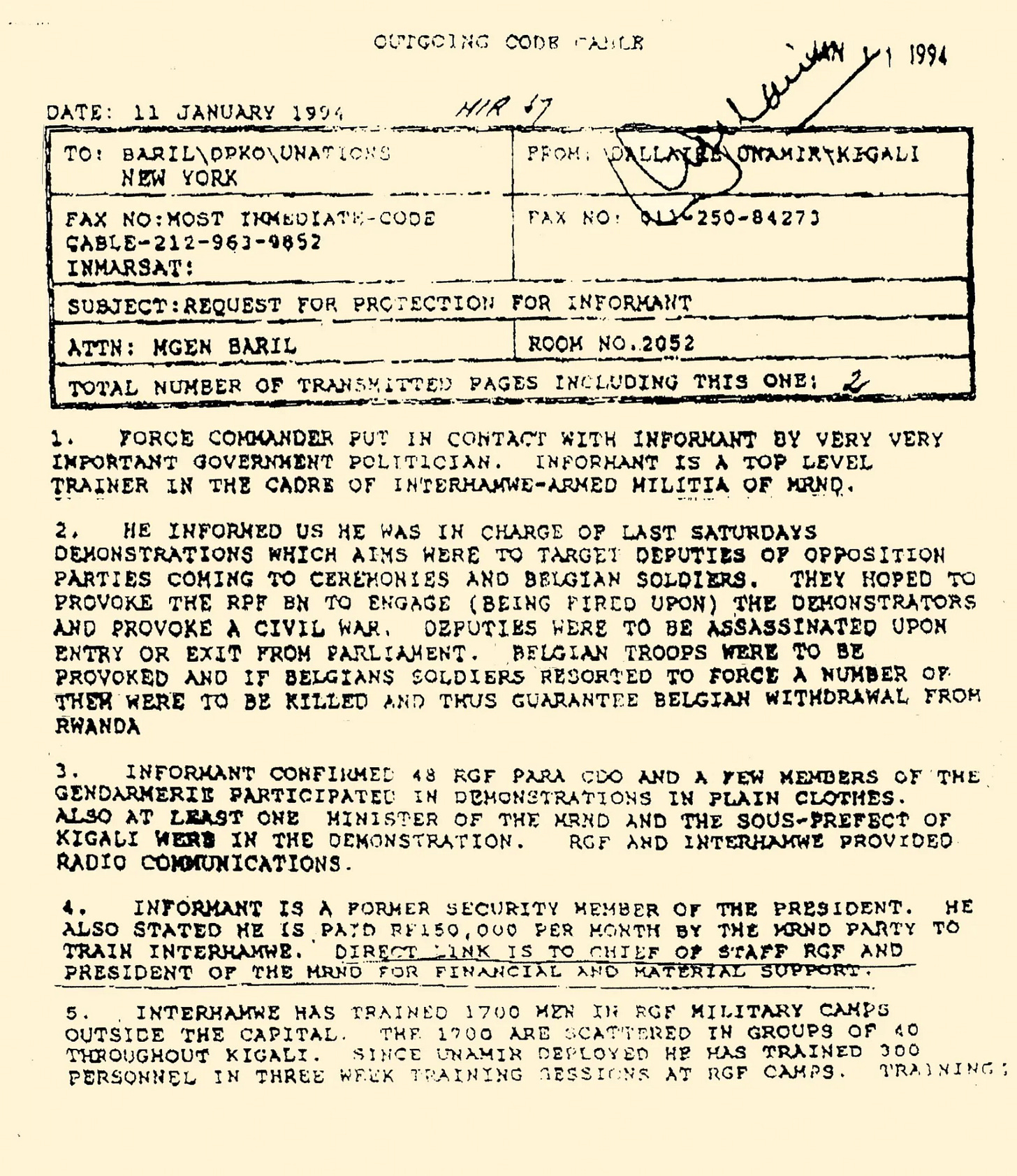

Worse, the U.N. force commander in Rwanda, Major General Roméo Dallaire, actually sent a fax to peacekeeping headquarters in New York three months before the genocide began, warning of the bloodshed to come. Dallaire’s fax “reported in startling detail the preparations that were under way to carry out precisely such an extermination campaign,” Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker in 1998.

Hence genocide guilt.

When I spent time in Kigali in 2014, Rwandans told me that the lights along the roads were only installed after the genocide. That the capital used to go completely dark at night. Those lights were metonymy for a more polished, wealthier city.

Still, it was impossible to talk to anyone without realizing that, if they were maybe 23 or older, they had direct memories of the genocide. There are gruesome memorials to the mass murder everywhere people were killed. I left Rwanda wondering how an entire country grapples with such a horrifyingly recent trauma, and devoted myself to trying to answer that question after I returned home.

It wasn’t just that the horrors were still fresh in people’s minds, it was that all was not calm — and is still not calm — beneath the veneer of still waters. The genocide was a result of decades of mistrust between Hutus and Tutsis, who were only formally delineated into ethic groups by their Belgian colonizers when they were forced to start carrying ethnic identity cards in 1933.

Listen here to a podcast I recorded with a genocide survivor

Rwanda’s ethnic clashes started long before 1994, and afterward moved into the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, where Hutu genocidaires flocked to avoid being hunted down in Rwanda. These men shifted the killing to DRC, which is still steeped in violence today.

“People don’t talk about it enough… but the Rwandan genocide was like flicking over the first domino,” a human rights activist in the Congolese city of Goma told BBC News of the connection between violence in Congo and what happened in Rwanda.

The resentment that led to all this violence had been building for a long time. The Belgian occupiers favored the Tutsis for their lighter skin. While the Tutsis were a smaller population than the Hutus, the colonialists thought that they must have had white European ancestors, and, because Tutsis were the economically advantaged group (as cattle ranchers rather than farmers), they were the natural pick for leadership positions. Resentment among Hutus grew in this African country that is, ironically, part of the Rift Valley. The story of Paul Rusesabagina is bound up in all these tensions. And whether he is a villain or a persecuted hero is a complicated question to answer.

A little over a week ago, Rusesabagina’s wife, Taciana, described him in The Washington Post as having been jailed for “nothing more than using his voice.” She is calling on the U.S. government to push for her husband’s release on humanitarian grounds.

But is Rusesabagina a terrorist? Or is he simply a victim of the ongoing strain between Hutus and Tutsis? Is he a dangerous criminal, or simply a victim of Kagame’s intolerance of dissent in the country he rules?

Is Paul Rusesabagina the peaceful savior of Rwanda, or a man who carries out violent acts against his own state?

Coming in Part 2: What Rusesabagina has said about the FLN’s use of force, and how Kagame has gotten away with repressing people and squashing press freedom — while managing to remain a favored president by Western leaders.

On Chills, there are no ads, and no outside influences because of it. This is a subscriber-supported space that gives a behind-the-scenes look at how risky investigative journalism gets made, from a journalist with 20 years of experience. Read Chills for free, or subscribe for bonus content like this. You can sign up here. Thank you for supporting independent journalism.

History seems replete with examples of crimes against humanity that erupt on every continent. Humans spend more time creating artificial and ever-shifting divides for money, power, land, endless grievances. I don't know how our own death-spiral will end, but imagine reading history 50 years from now...how the US fell into autocracy, vigilantism, and chaos because half the country was dead-set against life-saving vaccines and believed wokeness was more dangerous than fascism. I'd like to believe that weekly global warming catastrophes will finally release us from the insanity of this timeline, but history suggests (as with the fax you cite) that we will disregard the warnings about both democracy and climate until it's far too late.

Wow, really fascinating. How grim and strange to stay in that hotel, good on you. Thanks again.