Ransomed Al-Qaeda Hostage Speaks Out

A guest post from Jeff Woodke: Part 1 of 2.

Fearless reporting, a behind-the-curtains look at how journalism is made — and an unabashed point of view. Welcome to Chills.

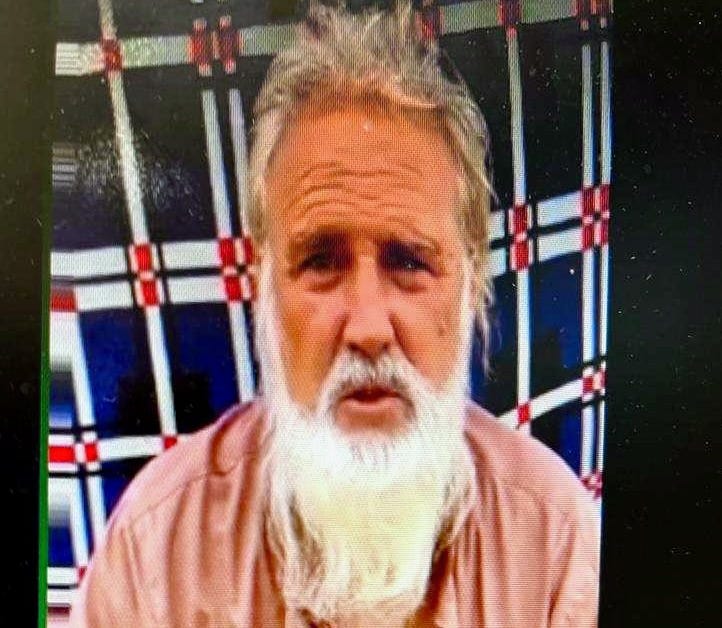

Rain soothed my morning as I woke and made my coffee. I sipped it slowly to the chatter of water in the downspouts and the soft light of a candle that smelled of quiet and pie. The shock of the election a week or so earlier was fading to a dull numbness. It was Nov. 13. I was 64 years old. Falling water was as a birthday song to me. Most of my birthdays over the past eight years had not been so peaceful. On Oct. 14, 2016, I was kidnapped by Al-Qaeda terrorists while at work in the town of Abalak, Niger. They took me hundreds of miles west to northern Mali, where they kept me as a hostage for six years, five months and five days. Birthdays came and went there, along with all hope I had of ever leaving that place alive.

I’d worked in Niger for over 27 years when I was taken. I ran a Christian humanitarian organization there, serving the nomadic pastoralists in the Abalak region. We did about everything imaginable, from digging wells to helping communities adapt to climate change and reduce drought disasters. We kept people alive in famines and made sure young nomadic girls had schools to go to and medical care. My wife and family worked with me although we had shifted our permanent residence in 2006, when my youngest kids hit high school. We moved to McKinleyville, a small town in Humboldt County, up in the northern woods of California. I went back and forth, alone, from home to Niger — until an orange muzzle flash from an AK-47 ripped through the dark night and I was captured. Men became ghosts that night; my friends died. They were torn from life. I was torn from reality.

I’ve written a memoir about my time in captivity, called From Nowhere to Forever. It’s my story not only of how I got through the ordeal, but also of how I confronted my own inner demons of depression and insanity. How I survived and forgave. Below is an excerpt.

Human trafficking is wrong. Treating humans as commodities for exchange is evil, no matter what the group is that does it, their reasons or rhetoric. If I manage to stay alive until my next birthday, I hope I’ll wake that morning, in a world with no more hostages, and where all of us are treated with humanity and respect.

— Jeff Woodke

Murderers’ Academy

The kouffar fell dead like unholy flies. They were the “unbelievers,” the miscreants worthy of death. Khalil’s smile got larger as they died. He squeezed the trigger, putting another round into a seated man’s chest. Joy mixed with unquenchable rage filled his mind, a special state of holy wrath. If jihad has a nirvana, this was it. Killing unbelievers. The American kafir was flat on the ground, ducking as a coward would, at least in Khalil’s estimation. He was their prey. The others, the guards, were just added blessings. Their deaths would gain him and his brothers in combat better places in paradise. He heard the infidels’ cries as they died and simply fired another round. He felt nothing for them; feeling had left his heart long ago. A lion felt nothing for a gazelle, except hunger.

Khalil would gladly have kept firing, blowing bits off the terrorized men, turning them into dead things with glee, but something stopped him: the American, the fat, cowardly American, got up and sprinted. Khalil turned, motioning to his partner to follow. They both knew what to do. They wouldn’t let the American escape. He may outrun them but he wouldn’t outrun a rifle round. He was not to die if possible; the emir had other plans for him. They gave merciless chase.

The American was me. Some weeks after my kidnapping, I’d had the occasion to speak with Khalil, asking him about the night he took me, asking why he’d killed my friends. I learned then of his thoughts, feelings and motivations as he joyfully recounted the event from his perspective. In his mind, he was a holy warrior doing his god’s work. Now he had bragging rights. He added with assurance that if they had not caught me when I ran, he would have put a round in my head from a distance. When he’d finished his story, I asked him why he had killed fellow Muslims, my guards, one of whom was a civilian.

“It’s Allah’s will that they died that night,” he said. “It was their destiny. They weren’t good Muslims, they worked for the government.” Shrugs and hand gestures of denial flowed along with his words. “They died for that sin, as Allah wills.” He justified the murder and barbarism with such ease it shocked me. My mind struggled to understand this way of seeing things, it was so different from my own views. To me, life was sacred. To Khalil, taking life was sacred.

“My guard was no soldier; he wasn’t armed, and he was a good Muslim,” I said, angry and frustrated with his facile answers as much as with his joy at murdering my friends. His happiness in having done it was making me sick. I knew the Koranic punishment for killing a Muslim — death and hell afterward. So, I reminded him of it. “Killing my friend was a sin! You…you,” I emphasized, anger turning my words to barbs. “You are a kafir!”

“You don’t know anything about Islam, and you are the kafir,” he said. “I made no sin; I did Allah’s will. You are the one going to hell, unless you repent and accept Islam.” Khalil wasn’t angry. He kept smiling a big smile but in his feral eyes murder lurked. As he walked away, I wondered where on earth the terrorists found people like Khalil, stone-cold killers. The answer, I was to learn, was that for the most part, they didn’t find them like that, they made them. As a zone commander from JNIM, an umbrella organization that unified all the jihadist groups in Mali, once told me: “Al-jihad madrassa” — “Jihad is a school.” A murderers’ academy.

Deserts, harsh and wild, know no empathy. Many of the desert’s animal denizens are equally as callous; it’s eat or be eaten. But humans are an empathetic lot, whether born in a desert or in Humboldt County, California, we know how people around us are feeling.

Yet knowing what someone else is feeling and giving a damn about it are two different things. Our empathy only extends so far. People who live in outside of our group can also live outside of our empathy.

A lack of empathy is a dangerous thing because it allows us to think of people outside of our group as enemies. You can kill enemies, or so the logic goes. To avoid dangerous conflict, the people of the Sahel have developed systems for social interaction between groups. There are unwritten rules taught from birth; how to greet a stranger, how to show hospitality or accept it. Things to say or not to say. What tribe you can exchange jokes with and what tribe you cannot. How to brew a pot of tea and savor salt with bread. How to flow in the current of nomadic life and not drown.

Khalil no longer had the desire to respect people from outside his Salafist group. They’d become his enemies, through no fault of their own other than the uniform they wore, or the type of Islam they believed in. In my case, it was because I was a Westerner. No matter my faith, views, beliefs or feelings, my status as a Westerner automatically made me an enemy in Khalil’s heart. As he walked away, imperious in attitude, impervious to blame, I realized that I’d never be able to connect with him, never be able to have a human-to-human conversation. He had no empathy for me. I was cut off. Shunned. An unholy outcast among holy warriors.

I watched empathy be deleted, like an old photo discarded from a phone, in another man. Hamza was his name. He was on one of the guard teams in the mountains, and was a sweet kid, like many I’d known in my years of working with nomads. He spoke kindly and with respect when he talked to me. In his culture, respect for my gray hair would have been taught to him before he could walk. Kindness showed in his eyes and acts; he helped me build my hut, despite scornful looks from the rest of his team. To them I was an animal. To Hamza I was a person.

Several months later, Hamza’s guard team rotated back in, as the teams in the mountains did. He’d changed. Certainly, he was no longer sweet. A cold darkness lurked in his eyes. It was the kind of thing that I’d seen in Khalil’s eyes: murder. His hatred of me was palpable, his behavior the polar opposite of what it had been. He no longer looked to help, but to hurt. Hamza had been transformed.

He was rude, aggressive and violent. I was sure he’d seen combat. Mujahedeen combat was guerilla-style, surprise attacks and often against civilians. Usually, they didn’t take prisoners. Instead, the wounded had their throats slit. I spoke to some mujahedeen who told me that cutting off a head was a rite of passage. You had to do it or face mockery as a coward. Such a level of aggressive violence does something to a person and, in my experience, the change is evident in their eyes.

Hamza, who’d never been to a formal school, had now been taught in other ways. A lack of schooling, common among nomadic children, makes them easy targets for terrorist recruiters. It keeps them isolated in a small corner of the world, cut off from other cultures, ideas and ways of thinking. I met many mujahedeen who had never even been to the closest large town as children. The only thing they had ever read was the Koran, and even that with difficulty. It’s easy to take a child from such an environment and teach him to consider non-Muslims the enemy. Extremists build on their lack of empathy, teaching them that the enemy must be killed. Most of the mujahedeen I’ve seen were teenagers, with some kids as young as 10 or 11, strapped with an AK-47. Eager to kill. Al-jihad madrassa. In the murderers’ academy, empathy is erased.

Jihad was a school indeed, and I had some things to learn. The first was how an empathetic person like me was supposed to live in a world without empathy. I mean, it was out there still, or should be, somewhere beyond captivity’s limits, past my chain-fixed borders. But empathy didn’t inhabit my world, the world of a hostage.

I’d always been empathetic but had a hard time expressing it. Trauma had put me in a kind of emotional cocoon as a kid, a bit of psychological bubble wrap that protected me. I could withdraw into it at times, letting whatever crisis was occurring go by. The downside was that it left me disconnected from those around me, to some extent. I suffered from this in high school and was a bit of a loner. Not engaging with folks didn’t mean I couldn’t read their emotions or understand how they were feeling. I could do those things very well. Consequently, when I connected with people, I could go very deep. But true empathy is not only being able to understand a person’s emotions and engage with them. There is a third and crucial component: action. We need to act so as to support the other person in their emotions. In this, empathy is a lot like love; they both require deeds.

That is the part I was lacking, and I found it in Christianity. Through Christ I understood that I was to take action to support others. If they were joyful or happy, I should help them express that. If they were hurting or in need, I should give them comfort or aid. No matter who they were, even if they were my enemy. That is a lesson I’ve realized takes a lifetime to learn.

Love is always expressed in action. This to me, was the central pillar of my faith, and what drew me to Christianity in the first place. This is what I saw Jesus doing in the pages of the Gospels. It made sense to me; if I lived like that, I would make the world a better place, and myself a better person. I spent most of my adult life working with nomadic people and trying to live out my faith among them.

For me, who’d spent decades trying to put empathy into action, giving my all to see it happen, the jihadist mindset was a punch, not a slap, to the face. These men were so unlike the people I’d been working with for so long. The delicate lattice of nomadic hospitality and respect for those not of the same group had been destroyed in relation to anyone who believed differently than them.

They were hyper-xenophobic and without care for those outside their group, the exact opposite of me in every way. There was an unbreachable barrier between the mujahedeen and me, one that I simply would never be able to cross. I could never become like them. I could never accept their version of Islam. My path was one of love, and I was psychologically, emotionally and perhaps physically unable to leave Christianity. That’s not to say that Christianity doesn’t have its problems and its own empathetic shortcomings. These were things that I would soon come to grips with, as my old life was deconstructed and erased. But I wasn’t quite to that point yet; I still had faith, hope and love, although hope was only slightly there and would soon disappear.

To be continued…

Chills is self-funded, without ads. If you want to be a part of this effort, of revealing how difficult reporting is made — of sending me to places like Ukraine to report for you — I hope you will consider subscribing for $50/year or $7/month.