‘It’s like Noah’s Ark. The doors are shut. No more animals are getting in.’

The mad dash to get journalists out of Afghanistan.

Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

The people who have risked their lives in the past 20 years to tell us stories of the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan are being left behind — and those trying to get them to safety are losing hope.

Thousands of foreign nationals are still being evacuated from Afghanistan, even as violence increases around the Kabul airport, including two explosions Thursday that killed at least 12 American troops and dozens of Afghan civilians, according to the Pentagon. And while these people have reason to be concerned about remaining in a Taliban-controlled country, such fears are an order of magnitude higher for the Afghans who worked — or who continue to work — with the U.S. and other NATO countries as media workers and translators, as it is for all Afghan journalists. Nobody likes a truth-teller in a time of coverup.

One group that, surprisingly, has hundreds of staffers and their families stranded in the country is the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which runs the pro-democracy Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

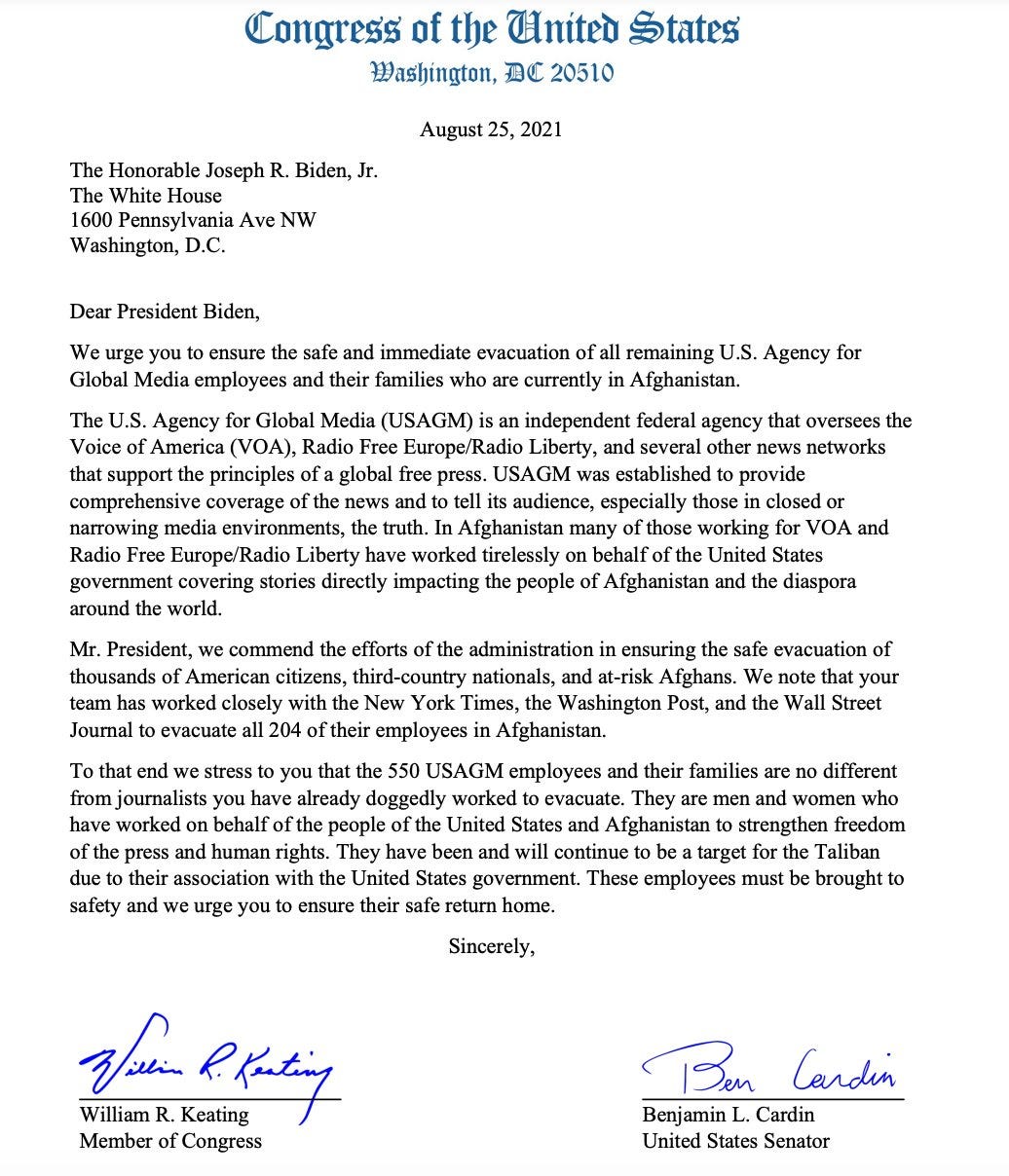

On Wednesday, 67 members of Congress sent President Biden a bipartisan letter saying that these staffers are being forgotten. “We stress to you that the 550 USAGM employees and their families are no different from journalists you have already doggedly worked to evacuate,” the letter reads.

I’ve been hearing from fellow journalists who are trying to get their own colleagues out of Afghanistan that there is a much higher number than 550, but, like everything in this shambolic pullout, the truth is obfuscated.

A spokesperson for VOA told me that, for security reasons, the broadcasting organization is “unwilling to provide specific details in response to your query, but know that VOA is working with USAGM and other authorities to ensure the safety of all of our personnel in Afghanistan.”

Also on Wednesday, a source told me that a group trying to get VOA staffers and other vulnerable people out of Afghanistan ran into a wall because the evacuees were unable to get into the airport. The group, which consists of humanitarian aid workers and former embassy and U.S. Agency for International Development officials, has two charter flights that can carry 340 people each. The organization is holding them in Kabul, for now, they said, until Friday.

Twenty-five VOA journalists said that an embassy official at the airport’s north gate told them that “only AMCITS, LPR, direct local hires could come in,” aka American citizens, lawful permanent residents, and staffers directly hired by VOA or RFE/RL. This, despite the fact that the U.S. government has worked with media outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post to evacuate their staff. Basically, the government is not extending the same privilege to their own employees.

The letter from Congress underscores that the VOA and RFE/RL journalists are desperate: “They have been and continue to be a target for the Taliban due to their association with the United States government.”

Multiple sources told me that they aren’t even sure these organizations have until Aug. 31, the official date for the Americans to leave the country, to get their staffers out. The U.S. needs time to evacuate the military, leaving civilians with what may be a shorter window. No one knows definitively, and those who should know — State Department, Defense Department and White House officials — are not responding. They may not even know the reality themselves.

Thursday’s tragedy — and the ongoing casualty count — is not making things any easier. The noose is not just tightening, it’s more like the hangman has one foot off the platform.

All journalists in Afghanistan, no matter who they work for, are at an extremely high risk of retaliation. “As the Taliban [has] extended their control over the provinces we have seen them close down media outfits and substitute their own personnel,” said Steven Butler, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ Asia program coordinator. “That hasn’t always led to people being killed or put in prison necessarily, but nonetheless journalists in Afghanistan are concerned that they are going to be pushed out of their profession — at the minimum. There are a number of very prominent journalists who have been harassed or chased by the Taliban and who have gone into hiding.”

The Taliban has posted armed soldiers outside the compound of Tolo News, the country’s most prominent TV station. CPJ has documented raids on the homes of at least six journalists in the last week or so. Women journalists have been taken off the air, as the Taliban militants threaten them with violence and brutality. Human Rights Watch’s Heather Barr has said that the Taliban is going house to house looking for journalists.

In this madness, I’ve been talking to friends and colleagues at media outlets and press freedom organizations to try to get a sense of what is being done to get people out. The mass panic is unprecedented, they say. Envision hundreds of tiny efforts so frenzied that the picture is just static. It’s a scramble to get everyone to safety, and the refrain I keep hearing over and over is that the U.S. government has royally messed this up.

“Not only is it difficult to get people to the airport,” one friend told me, “but, at this point, it’s hard to even know what you’re risking your life for. When you get to the gate, will there even be a gate?”

There’s only so much that press freedom organizations and news outlets can do; they can’t evacuate people, and they can’t issue visas. They are doing what is within their limits.

CPJ “has intensified collaboration with U.S. and other government officials and our global network … to provide emergency assistance, and connect them with resources and support to get out of the country if they are trying to leave,” Bebe Santa-Wood, a CPJ spokeswoman, told me.

While CPJ has expanded greatly since I worked there from 2007 to 2011, it is still a very small group with limited resources. I know their emergency team, and they care tremendously about their cases, and are absolutely crazed right now, as is the whole organization. I know that some of my former colleagues don’t sleep at night, working on such things around the clock. Butler said they are receiving “hundreds and hundreds” of pleas for help from journalists (and others) daily.

The U.S. government has had time since at least April, when the military drawdown was announced, to start getting visa applications and exits going. But that’s not what happened, and nobody has been able to tell me why, exactly. For many journalists, the slow pace of evacuation is potentially deadly, with women and ethnic-minority journalists at the highest risk. One female journalist told CPJ that if the U.S. finally decides to evacuate her, “I may not be alive by that time.”

While the State Department has created a special visa program to (hopefully) expedite the resettlement process for Afghans who work for U.S. media outlets, those people have to get to a third country before they can apply. Then there are the Afghans who work for Afghan media outlets. They can apply for asylum, but those people have years ahead of them in a backed-up refugee pipeline before they can realistically consider leaving the country.

“A generation of Afghans are losing their dreams,” a U.S.-based media colleague and friend told me. She is feverishly trying to help a stuck journalist friend and his family. Like a number of people I spoke to, she is despondent. Avenues to a life in a free country are closing quickly like choked arteries in a human heart.

A woman from the group of humanitarians with the charter flights told me that they are hearing reports of Special Immigrant Visa holders — usually U.S. government-employed Afghans, but some journalists as well — being turned away at the airport, in addition to the sundry thousands trying to escape an uncertain, but certainly more restrictive and violent, future.

Everyone I spoke to — whether press freedom advocates or journalism colleagues — is pulling every string they can find, even the ones that are just shreds. But it’s chaos, and it’s not fixable in the days — or hours — journalists have left to definitively escape retribution, many say.

“It’s too late,” my friend said. “It’s like Noah’s Ark. The doors are shut. No more animals are getting in.”

This story first appeared in the Washington Monthly.

On Chills, there are no ads, and no outside influences because of it. This is a subscriber-supported space that gives a behind-the-scenes look at how risky investigative journalism gets made, from a journalist with 20 years of experience. Read Chills for free, or subscribe for bonus content like this. You can sign up here. Thank you for supporting independent journalism.

Hope, and sending all journalists a prayer, and a hug. Thanks for this. Very sobering.

Heartbreaking.