In Ukraine, WWII survivors struggle

Almost 80 years later, those who were young and witnessed the last extensive land war in Europe try to live through the current one.

Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

You can support my Ukraine reporting at this GoFundMe. Thank you.

HORENKA, UKRAINE — A chunky yellow Labrador comes bounding down the sidewalk and into the street toward me. Trailing behind him is an older man repeatedly calling the dog’s name in Ukrainian: “Richi! Richi, come!”

The dog wants no part of going home while people are willing to pet him. Finally, the man, Petro Virko, 81, catches up with Richi and drags him by his collar down an entire block, back to their house. Or, I should say, to their self-built compound. When you’ve got an outdoor sauna, a carpentry workshop, a greenhouse and an underground bunker with more than one full bar and a rifle range, “compound” seems more appropriate.

Virko invites me in, but before he does, he stops in his leafy front garden to point to the spot where his adored previous Labrador, who was rusty red and 16, died a few months ago in a shock wave from a Russian bomb.

“It was probably a heart attack,” Virko says, his voice full of grief. He deeply misses that dog, who was also named Richi. The rambunctious yellow Lab he now lives with was found in some trenches nearby — his full name is Richi II.

Virko sees me and my fixer into his house. So now we’re sinking into dusty couches in his darkened, mildewed home in Horenka, a suburb about a half an hour northwest of Kyiv and about 10 minutes from Bucha. This village was the final front line of the thwarted Russian attempt to capture Kyiv. Bombed and invaded intermittently since Feb. 24, when the war began, the exhausted village, home to more than 5,000 people, held strong. Most people evacuated early; still, 33 have died, says Larysa Lishynska, a lawyer who put her job on hold to lead an effort to bring food and supplies to the village.

“You either watch,” she says, “or you help.”

Locals estimate that there has been damage to nearly 80 percent of the structures in Horenka; like so many villages that surround Kyiv, shattered windows are the norm, and, in a perverse kind of comedy, it seems like every other house has been destroyed. Unlike in neighboring villages, such as Bucha and Irpin (the sites of well-publicized massacres), in Horenka, I did not hear about people being shot in their cars as they fled.

When the Russians pushed toward Kyiv after landing at the nearby Antonov Airport — a key target in Russia’s goal to create an air bridge that would allow them to take the capital — soldiers went from house to house in these suburbs, taking with them everything from ovens to fishing poles as they searched for patriotic Ukrainians by making them strip. The idea was to find military and pro-Ukrainian tattoos. I’ve heard reports about men being tortured and killed because of such ink.

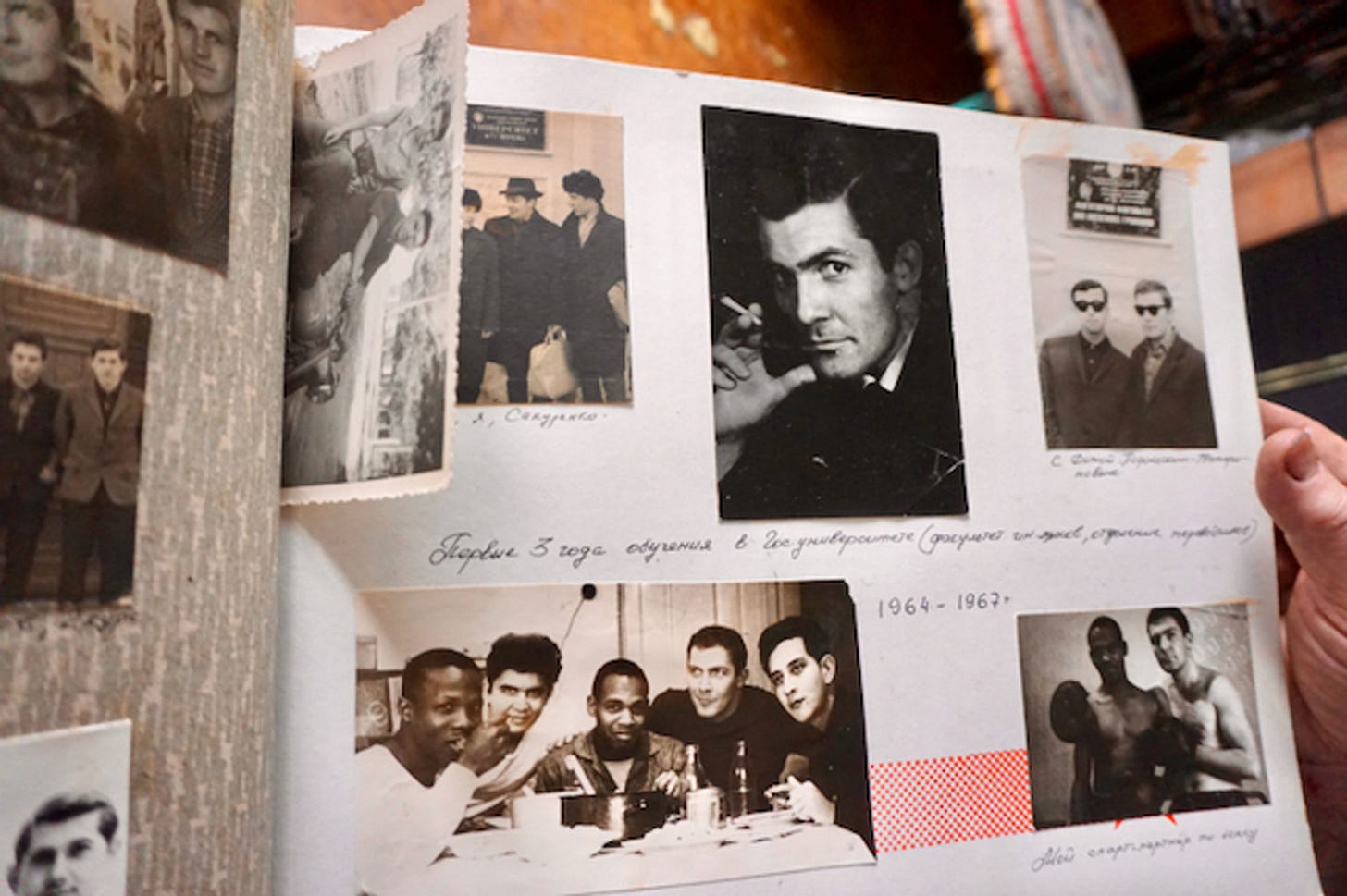

Regardless, Virko was one of a handful of men who stayed behind. He’s the stereotype of the cranky old man standing his ground: “It’s my house, my land, and I won’t leave it,” he says. Actually, replace “cranky” with “resourceful.” Like some of his neighbors, he’s old enough to have memories — however faint — of being in Ukraine at the end of World War II. And now he’s living through a near-facsimile of that period’s hungry aftermath. This time, though, he’s prepared for it, having stocked up and canned and pickled every vegetable imaginable.

Besides, he says, he wasn’t about to leave behind his dog — it’s just the two of them these days. His beloved wife died of skin cancer in 2004 from, he believes, radiation released during the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986. And, horrifically, his mother died in a massive 1961 landslide in Kyiv that some called the “revenge of Babyn Yar,” the site at which Nazis killed 100,000 Jews, Roma and political prisoners. A couple of months ago, Russians bombed a communications tower that overlooks the ravine. Some said Babyn Yar was hit, but it may not have been. I saw the damage to the tower, but not the site itself.

The term “fog of war” exists for a reason.

Please click over to New Lines Magazine to read the rest of this story.

On Chills, there are no ads, and no outside influences because of it. This is a subscriber-supported space that gives a behind-the-scenes look at how risky investigative journalism gets made, from a journalist with 20 years of experience. Read Chills for free, or subscribe for bonus content like this. You can sign up here. Thank you for supporting independent journalism.

The world is insane. These people were born into a world where innocents are slaughtered, and have to relive that trauma at the end of their lives. And a whole new generation of kids will start this horrific cycle all over again. We are not a civilized species.

Putin is a monster and Russians are empty shells of humans...flourishing on propaganda or cowed by fear. The West has barely risen to the challenge, while Americans have normalized genocide, as they normalized 1M+ Covid deaths, the slaughter of children in schools, the unimaginable toll of the opioid epidemic, the rise of US fascism, and the apocalypse of global warming. It's impossible to believe that Americans saved the world 80 years ago. We are literally incapable of preventing the deaths of our toddlers in schools.