Journalism is too opaque and misunderstood. Chills gives a behind-the-scenes look at how dangerous investigative journalism gets made.

One of the nasty fallouts of the Trump years is that Americans’ trust in the media has plummeted. An October Gallup poll shows that just 36 percent of the public have confidence that we report fairly and accurately. And while that number hasn’t been over 50 percent since 2003, it’s also only been lower once, in 2016.

To say this is frustrating to me and other journalists is a massive understatement. It drives me absolutely bananas. The vast majority of my colleagues are diligent, brilliant, careful, thorough reporters. Beyond being attacked as writing “fake news” for the past five years, I’ve been called every name in the book, often by people who have never even read a word I’ve written, including literally yelling at me on social media that I — not the outlets I write for — I am fake news. As in, “You’re fake news!”

While I have a fair share of anger at the cable news industry for duping Americans into assuming that all journalism is just punditry or opinion — I also know that it is incumbent upon us in the profession to explain why — and how — we do what we do. Hence, this site.

One thing I think is widely not understood about journalism is how we use “off the record,” “on background,” and other such designations attributing information to sources.

While recently reporting a story, I spoke to a government spokeswoman. She immediately said that everything she would say would be off the record and that she’d give me an on-the-record statement after. I agreed, which may have been stupid. It’s a tactic I’ve long taken while interviewing traumatized sources — of course they can tell me what they want and then we can negotiate what they feel is comfortable for public consumption — but politicians especially must be pressed hard to stay on the record, if not “on background.” (I’ll define that shortly.)

In any case, I followed up with this spokeswoman three times before publication, asking for that statement, but she never sent it. Also, when we talked, I asked her how I should identify her in my story, which is something I ask all sources. She said I shouldn’t use her name and just call her “a spokesperson.”

“A spokeswoman?” I said, that having been the Associated Press style for decades: identifying whether the person is a man or a woman. (Although, as of 2016, it now accepts “spokesperson” too.

“No,” she said. “Just use ‘spokesperson.’”

Ugh. Her insistence added another layer of obfuscation I didn’t appreciate. All it said to me was that she didn’t want to be able to be identified in case she said something that could get her into trouble … in her own carefully written statement … which still didn’t even exist.

“Off the record”

This means you can’t use anything that person says. So what’s the point? There is one.

An off-the-record interview is a way of learning information that can guide your reporting. Basically, it’s like someone saying, “You didn’t hear it from me, but…” It just means that you’re going to have to verify what they’ve told you — and, hopefully, get someone else to say it on the record, or, at the very least, “not for attribution.” (See below.) But you cannot, under any circumstances, print off-the-record information, or even tell someone else what you know from an off-the-record interview.

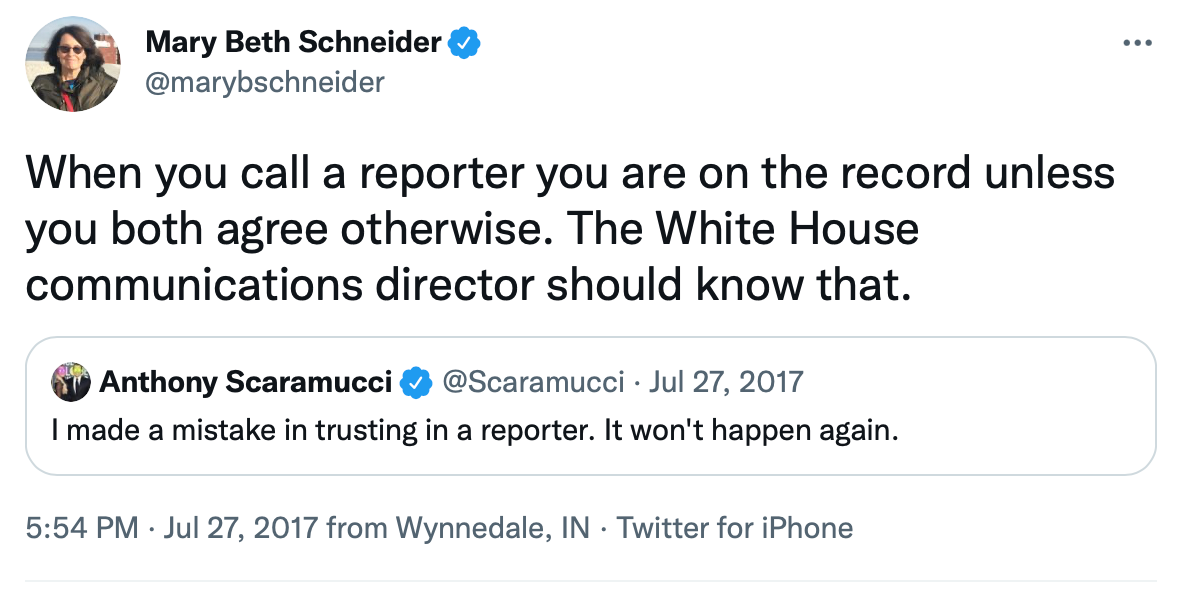

Important point about this designation: Every conversation with a reporter is on the record unless a source specifies at the outset that it is not. Because people outside of government or public relations often don’t know this, I am usually open to negotiating with my sources after a conversation about what I will use. Most journalists do not do this, but in the kind of reporting I do, I am usually either protecting a vulnerable source, or trying not to alienate one. But I make this call on a case-to-case basis, and would almost never allow a government or PR source to retroactively take something off the record.

A good reason to not go off the record was offered by Dean Baquet, The New York Times’s executive editor, in 2018. That year, President Trump met with A.G. Sulzberger, the publisher of The Times. Baquet refused to attend the meeting.

“As a rule I don’t go off the record with high-ranking officials, particularly the president,” Baquet told Buzzfeed News. “As the person overseeing coverage, I don’t think officials should be able to tell me things that I can’t publish. And I don’t want to be courted or wooed.”

Part of a journalist’s job is to ensure the transparency of governments.

“Not for attribution”

This means you can quote what someone said, but you can’t identify them. So you describe their position, call them something general, like “a senior White House official” or “someone who has lived in Brooklyn for two decades,” etc.

Using an anonymous source is tricky. You have to weigh the importance of the information and whether the source will face retribution if named. Sometimes an anonymous quote hurts a story more than it helps, by allowing readers to question whether it was made up to suit the writer’s needs.

“On background”

This is probably a less understood sourcing term.

Sometimes, this is the same as “not for attribution,” but not always. Instead, it’s a condition journalists negotiate with each source.

You may be able to give general descriptions of the person or their job, in a way that they cannot be identified — if the source agrees. “On background” can mean this, or it can mean that the information you glean can be published, if not quoted, and certainly not attributed directly.

“Deep background”

This is the really weird one.

The AP’s definition: “The information can be used but without attribution. The source does not want to be identified in any way, even on condition of anonymity. In general, information obtained under any of these circumstances can be pursued with other sources to be placed on the record.”

If your head is spinning, so is mine.

William E. Lee, a journalism professor at the University of Georgia, explained in the school’s newspaper that it’s generally used “by officials at the highest levels of government who want to disclose information to the press without attribution. Such material can be published, provided there is no identification of the source or how the material was obtained.”

Lee pointed to the Valerie Plame story as an example in which deep background material was used: “President George W. Bush authorized [Scooter] Libby to disclose key classified information solely to The New York Times’s Judith Miller, who was viewed favorably within the Bush White House because of her pre-Iraq war reporting,” he said. “Among Washington insiders, the authorized disclosure of classified information to selected reporters is known as ‘planting.’ This is distinct from leaking, which is the unauthorized disclosure of classified information.”

With tinges of the other designations smushed in there, “deep background” is a term that has shades of “off the record” or “on background.” Most journalists I know, unless they cover politics, don’t use this as a term while reporting.

Yes, some of this system of attribution is perplexing — and certainly subjective. That’s the thing about journalism: It can come across as inconsistent and tentative, leaving readers to wonder if we’re just making up the rules as we go along. But the profession is basically about being a transmitter and translator of what other human beings do and say, so as long as we keep the lines of communications clear when talking to sources, we’re doing the best we can to ensure the integrity of the process.

After all, with so many choices to make as we report and write, there is always going to be some compromise in the practice. It’s our job as journalists to bring as much transparency as we can, both to our reporting, and to how we present what we find to readers. And, knowing that 100 percent transparency is impossible when a term as cryptic as “deep background” exists, it’s up to us to spread media literacy.

Being the fourth estate of democracy means that we, for all intents and purposes, work for you.

On Chills, there are no ads, and no outside influences because of it. This is a subscriber-supported space that gives a behind-the-scenes look at how risky investigative journalism gets made, from a journalist with 20 years of experience. Read Chills for free, or subscribe for bonus content like this. You can sign up here. Thank you for supporting independent journalism.

Holy smokes. Thank you so much for the dictionary! Who knew something like deep background existed? I never heard the term, nor would have been able to figure it out without help.

This piece gave me a greater appreciation for journalists who do their homework and look out for their sources. But I can't imagine how frustrating it is to be told something and then not be able to report it. I understand the principle but the temptation must be fierce.

As always, I learned so much. Thank you again.