How Media’s Racism, Indifference and Finances Affect Countries at War

There is a chicken-and-egg problem between media outlets and the people who consume their content.

Fearless reporting, a behind-the-curtains look at how journalism is made — and an unabashed point of view. Welcome to Chills.

Why don’t we know (more) about the largest displacement crisis in the world? It’s in Sudan and the surrounding countries, and 10.7 million people having been driven from their homes because of 17 months of war already.

Why aren’t we doing anything about the atrocities — alleged genocide and systematic interethnic rape — being committed in Sudan and in the countries to which Sudanese men, women and children have fled?

Why isn’t there a rush to donate to help the hundreds of thousands of people who are currently living through famine in a North Darfur refugee camp?

NB: The warring parties — the Sudanese army and its former paramilitary ally, the Rapid Support Forces — began a brutal power struggle in April 2023, and the war shows no signs of stopping. See this summary from the Council on Foreign Relations to learn about the complex religious and political history of the stop-and-start conflict in Sudan.

As a journalist for the past 25 years who has reported mainly on war and sexualized violence, I have been frustrated time and again about why the media will not cover or maintain coverage on human rights and war in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing parts of the world. As a freelancer who has spent years pitching outlets such stories, I’ve heard a lot of rejections that come with, “Oh, we just did a story on women in [insert nearby country].”

But at least we’re hearing everywhere about the 17 people who have died in floods in Central Europe, right?

I am not saying that fewer deaths and less displacement and tragedy are somehow less important than the deaths and displacement of millions. And I am certainly not saying the U.S. media shouldn’t report on the floods. What I find so disturbing in seeing news story after news story about the natural disaster in Europe is that what is happening in Sudan is man-made — and therefore can be unmade. If we’re paying attention. (And yes, you could also argue that the floods are “man-made” as well if you want to talk about urban planning and climate change.)

Conflict causes starvation, the destruction of cultural monuments and an endless violation of human rights, among other consequences. These are all things that can be worked on and, hopefully, stopped. International governments can intervene to ensure that humanitarian aid reaches people suffering, and they can facilitate peace talks. They can support civil society organizations that are working on the ground. And the American people can help too — but only if we know what’s happening. That’s why I’m so frustrated with my own industry.

Why Is Coverage So Sparse?

I believe one reason why barely anybody knows about the nightmares like the one in Sudan is because of the financial decimation of the press. Major news outlets have closed most of their foreign bureaus. The New York Times, which is financially healthier than most of its competitors, only has three bureaus in all of sub-Saharan Africa, and, as far as I know, only a couple more full-time correspondents based there.

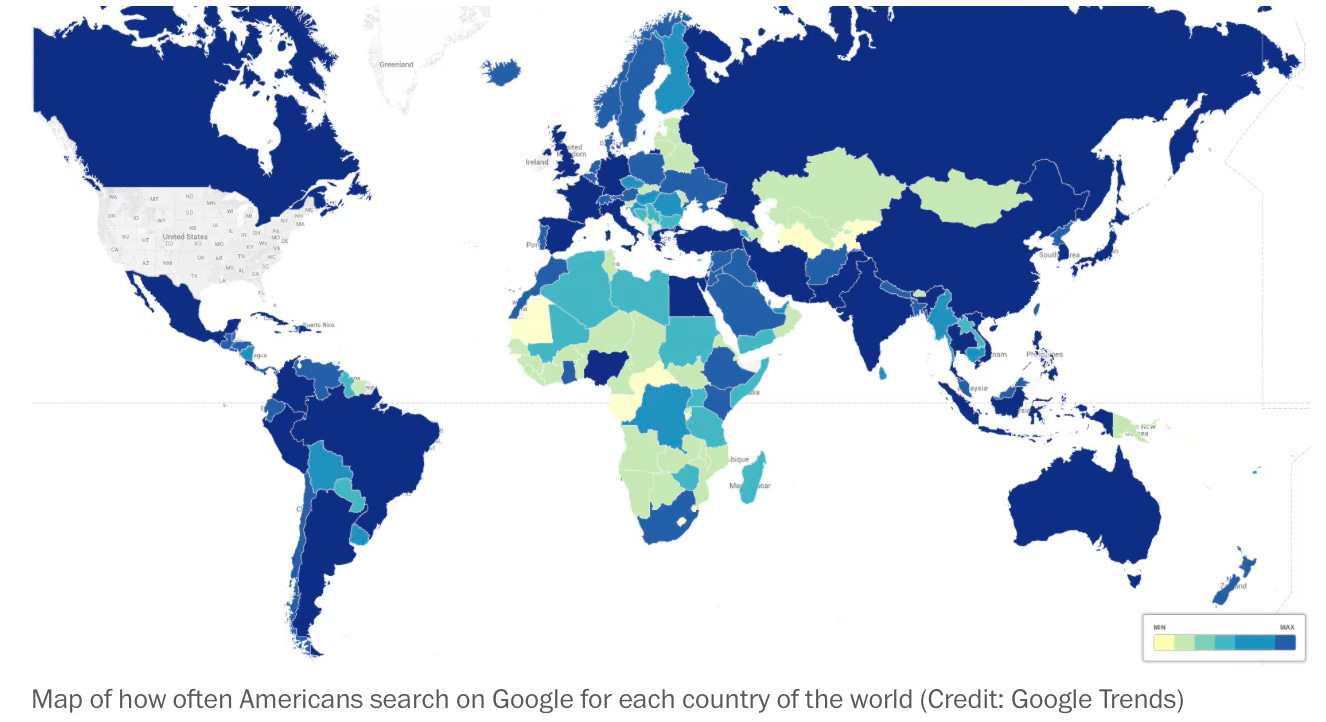

The conventional wisdom seems to be that Americans don’t tend to read Africa coverage, so editors devote few pages to it. This is going off my own observations, having worked with a lot of different editors over the years who have implied as much. Then there are these maps, which measure via Google Trends which countries Americans want to read about, published in The Washington Post in 2016. Sudan is in turquoise just south of dark-blue Egypt. South Sudan is below it in light green.

Which brings me to the obvious problem, which is so obvious, I probably don’t have to say it. But saying it is better than not saying it: racism. Just look at the valley and hill of coverage between the overlapping genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia.

The Western media developed while many countries were steeped in colonialism and slavery. They were countries that were left behind as they declared independence after being raped and robbed. Who cared anymore what happened those places? And Westerners too often still consider the continent of Africa a faraway, dark-hearted land. It’s all just a big mush of bad in too many minds instead of a complex continent full of multitudes of cultures and foods and landscapes.

Then there’s the wee problem of the lack of diversity in Western newsrooms, which inherently influences who writes and publishes what and how and where. Here’s an insightful read by Jelani Cobb on why diversity in newsrooms matters, one of many that has offered some insight to me as a white journalist trying to do this work.

Western editors also often consider every story from the entire continent of Africa to be the same story, or part of the same story, and so they don’t devote much space to it. Every story from Africa is as discrete as every episode of “Law and Order: SVU,” but the victims in “SVU” are usually white, often rich, and almost always American, so we are primed to think of them as individual people with unique stories — whereas too many people have been primed to think of all African people as having the same, impoverished origin.

And, while an editor’s news judgment may be sound, perhaps they know (or think they know) that a story about Sudan isn’t going to sell newspapers. They believe it is important and should be published in their outlet, but maybe it just shouldn’t be a promoted as a top story.

In the end, it comes down to a chicken-and-egg kind of thing. If journalists believe readers don’t care about places like Sudan, they’re not going to cover it. But if outlets don’t write about places that are “hard” to cover, then readers will never have a chance to learn about the fascinating intricacies and the beautiful, and painful, lives people around the world live. If they did, it would (hopefully) create more reader interest in hearing such stories, which would cause media outlets to spend more money and devote more room to publishing them, which would then, perhaps, lead to consumers’ outrage and, one can only hope, pressure on governments to do more — to do anything — to stop these horrors.

Parts of this article were adapted from a post I wrote in 2021. You can read it here.

Chills is self-funded, without ads. If you want to be a part of this effort, of revealing how difficult reporting is made — of sending me to places like Ukraine to report for you — I hope you will consider subscribing for $50/year or $7/month.

You write from a perspective few other people have, and explain things to the rest of us in ways that we can understand. Thank you for writing this.

I agree it certainly is a chicken and egg scenario. Most people can't identify where Sudan might be on a map, much less care about the mass killing going on there. We don't have a connection with Africa the same way we do with Europe or Asia, or even to a lesser degree South America. Many Americans have moved on from the Ukraine war, when I bring it up to people, they look at me like I'm nuts.

Africa isn't on the top 10 places people go to visit or even know the cuisine. I thought when Oprah founded her school in South Africa it might open up interest there, but unfortunately that didn't happen. I don't see this changing anytime soon either, there aren't news bureaus there, so nothing is reported to us, and isn't it the news industry's job to tell us what we should care about? (highly sarcastic statement) Until it affects us, we are disinterested. And without our interest and involvement, evil takes place with impunity.