How a journalist chases a monster, Part 10

Will it be safe to attend the trial, or will I be killed? Meet my savior, Yves.

Read Part 1 of this series here. It will give you background on the story of the girls that this backstory is dependent upon.

It was September 2017, three months after the arrest of Batumike and 67 of his men for the abduction and rapes of nearly 50 girls in Kavumu. His trial and that of 17 others was set to begin in mid-November.

There was no way I was going to miss this, not after reporting on the rapes of the Kavumu girls for almost four years. So I began doing my normal course of due diligence when I plan a reporting trip in a dangerous part of the world, focusing on two questions:

1. How safe was the eastern province of South Kivu, where I’d be going, at that point? Had the war shifted into the province from up north or out west? (That is always an issue when visiting the Democratic Republic of Congo: The war is an ever-slithering, multiheaded snake, with the many militias and the often dangerous Congolese Army — the FARDC — constantly moving and fighting in various locations.)

2. On top of that, what were the national and local political conditions, and how would any protests and other unrest affect me?

Here’s what I found out:

1. The war actually had begun to dip into South Kivu. Not Bukavu or Kavumu, where the trial would be held, but who knew where fighting would break out next? This was different than the peaceful province I last visited nearly a year earlier.

2. In late 2016, after 15 years in power, President Joseph Kabila was supposed to vacate his office because of constitutional term limits. But he arbitrarily moved the election to 2018 in a refusal to give up his stranglehold on power, setting off massive protests across the country, many of which were turning deadly.

The country was also denying foreign visas a lot at that time and, worse, allowing journalists and aid workers to land at airports and immediately turning them back to where they came from.

Friends and family really didn’t want me to go back, but I told them that I was going through all the safety protocols and that I felt okay with the level of risk. If I got ejected from the country after landing, I’d deal with it. I had spoken to many sources in DRC who all felt it was safe enough for journalists to go.

Then, someone asked me something I’d already been asked repeatedly, but somehow tweaked my ear differently this time: “But are you safe in going?” Somehow, I had never heard the intent behind the question until that moment. What my colleagues and friends were asking was, “Is it really safe for you, as the journalist who put Batumike and his militia into the international news?” Ohhhhhh. Hm.

I made a few more calls. The short answer was: absolutely not.

“You think the militia would come after me?” I asked a friend in Bukavu.

“No,” she said. “I think it would be the government.”

That surprised me. But I was fine with it.

“That’s okay,” I told her. “I can handle being harassed by them.”

“No,” she said. “The government kills.”

I quickly decided that if I couldn’t be on the ground, I needed to hire someone to be there for me. Through connections in Bukavu, I found a journalist In North Kivu province who seemed pretty good, and we agreed on terms and payment (which came out of my own pocket. Freelancers do not get such financial support).

At the end of October, he ghosted.

I was screwed.

By Nov. 2, 2017, the trial was set to begin in seven days, and I still hadn’t found a new journalist to hire in Congo.

Finally, a friend came through for me. She put me in touch with the only person anyone could find in the vicinity of Bukavu who could be my stringer — aka my eyes and ears in the courtroom. His was a young man named Yves Kulondwa, and he was a journalist who spoke French, Swahili and some English. Perfect.

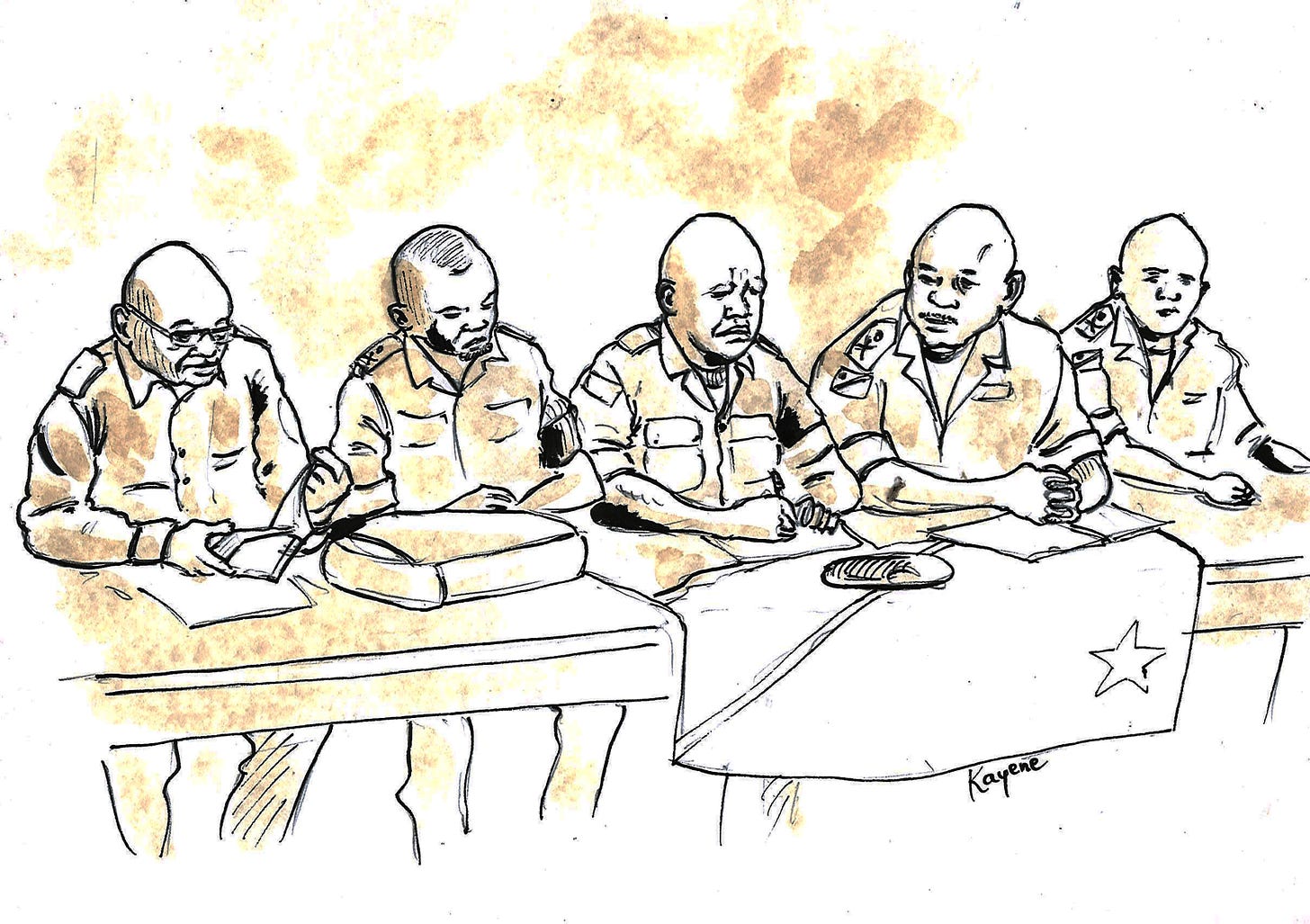

But there was a small problem (which felt massive in my gut). Yves, while working at a local newspaper, was not a reporter. Or an editor. He was … a cartoonist and a photographer.

But someone who could take pictures and tell me what happened each day was better than no one. Yves was all I had, so I emailed him and crossed my fingers.

On Nov. 3, 2017, I wrote to Yves, explaining what I was looking for — more than just a simple jotting down of words, I wanted to know what the room smelled like, how the people watching the proceedings behaved, etc. And I told him why I couldn’t be there myself.

He replied:

I'm still reading your posts, and I really understand why you wouldn't be well welcomed here!

Of course, your proposition sounds good for me, and I am ready to do that. Not just because I work for a newspaper that promotes women’s rights, but also because I am personally revolted by these atrocities.

Of course, I can describe emotions and attitudes in the court with words, but I think it would be better if I could “enrich” them with drawings. what do you think about [that]?

My gut rattled again. “Enrich”? I was starting to think my best hope was that he might be able to feed me just enough that I could do something with it.

After the first day of the trial, Yves sent me his first dispatch (which I have Google translated from French here):

Day 1

It is Thursday 09 November 2017. It is around 8:30 a.m. in Kavumu Center.

It rained the night before. Steam escapes from the still damp ground of the great courtyard of the old "LUSHAMBA" room, because the sun has already risen and is now burning slightly. This room, renamed EFFO PERSO, is located a few meters from the Tribunal de Grande Instance of Kavumu.

The opening hearing of the trial was scheduled to begin at 9:00 a.m. But it is already 10:20 a.m. and there is still no one in the courtroom, apart from the building manager, who gives instructions to a man who is crouching, cleaning the walls, which are stained with mud from the rain the day before ...

I. Was. Floored.

Yves was not only “better than no one,” he was good. Really, really good.

Even translated by an algorithm, his observational skills and his immediate interest in recording every big or small thing that happened was beyond valuable to me as a journalist trying to continue to tell this story from New York, 7,000 miles away. I have not published much about the trial until now, so please hang on for an upcoming week’s chapter, which will take you into the absurdity of the trial via Yves’s excellent reporting — and yes, through his incredibly beautiful cartoons and illustrations.

Read Part 11 of “How a journalist chases a monster” here.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

Speaking of enrichment, I continue to be enriched by your description all the things that go into into getting a story. They're much more than my naive notion that a reporter, usually dispatched by a powerful news organization, just shows up and takes notes. I'd never really considered the logistics and planning involved for freelancers, especially as it relates to personal safety. And I had no idea of the resourcefulness that the job demands, coming up with solutions such as finding a surrogate like Yves on short notice to serve as your eyes and ears (and nose) at a trial you knew you had to attend one way or another. Bravo!

Thanks for this continuing cliff hanger. Love Yves' drawing. Julie