Read Part 1 of this series here. It will give you background on the story of the girls that this backstory is dependent upon.

When I left off in Part 6, David Bodeli, the one Congolese police officer tasked with solving the ongoing rape of little girls in Kavumu, was talking about how the case haunted him. There were just so many terrible aspects to what was happening, and so many strange mysteries. One of the biggest was that entire families would not wake up while men entered their houses (some of which didn’t even have a door) and stole their daughters in the night.

The rumor circulating in Kavumu and the nearby city of Bukavu was that the men were sprinkling over the houses a kind of “magic powder” that put people into a deep sleep.

A belief in black magic, or witchcraft, is widespread in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A secret 1964 report by the Pentagon concluded that militiamen, who were in the middle of a rebellion against the government, believed they were impervious to bullets through the use of sorcery. In the struggle for control over the country’s uranium after the Belgian occupation collapsed in 1960, the United States wanted to look at whether they could weaponize the practices somehow. (Here’s an engaging read about that from writer Logan Nye at We Are the Mighty, a journalism site for the military community.)

Many Congolese Army members were (and still are) convinced that the militiamen were invincible, under various spells conjured by witch doctors who had imbued objects known as “fetishes” with magical powers.

The militias, of which there are hundreds, are known as Mai-Mai, which literally means “water water” — either because the men douse themselves in “magic” water to protect themselves from bullets, or because bullets are said to harmlessly pass through these men as if they were made of water instead of flesh. Over the years, Mai-Mai militias have kidnapped large numbers of women in both the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu (where Kavumu and Bukavu are located), taking them into the bush and forcing them into sexual slavery.

Objects such as wooden figures, gourds, horns and shells called nkisi are used as fetishes because they are said to contain magical material. Various militias in Congo also undergo initiation rituals involving “magic” water and scarification to give them strength on the battlefield.

And it’s not only the Congolese who believe in witchcraft. A Swedish doctor told me that after years of living in the country, she’d seen things she “just can’t explain.”

Locals had a lot of theories about what the Kavumu rapists were seeking specifically: When the men obtained virgin blood they would become “rich with red diamonds” or protected from guns. Some of the Kavumu mothers believed the rapists were trying to obtain some kind of “precious object” that resides within the womb and would give them strength.

There were also many who were firmly convinced that the “magic powder” that put the families to sleep was real.

One Kavumu mother said it took Dr. Denis Mukwege, Nobel laureate and medical director of Panzi Hospital, to disabuse her of the idea that her daughter’s attack had something to do with accumulating money.

“He said it’s not because of wealth,” she told me. He was very clear to her: “This is rape,” he said.

Combine a strong belief in witchcraft with a never-ending war and a traumatized population, and the mix is combustible. But those who believed there was some kind of “magic” involved in the attacks would, in a way, be right.

David Bodeli and I were still sitting on a terrace above Lake Kivu, listening to the screech of bugs between our words.

I’d been wondering whether there was potentially some kind of sleep-inducing herb growing on the nearby Bishiburu plantation, where the longtime German owner, a botanist named Walter Müller, was murdered in 2012. Over nearly 40 years, Müller had made a family at the plantation while working for Pharmakina, an international pharmaceutical company based in Bukavu. The company mainly produced quinine — a treatment for malaria — from the bark of cinchona, or feverfew, trees.

In Müller’s time, Pharmakina allegedly produced other drugs besides quinine, but I couldn’t confirm that in a later visit to its headquarters. Curious if Pharmakina might still be connected to the plantation after its takeover by the militia that killed Müller, I also asked whether local farms supplied materials to the company. The executive I spoke to refused to answer a single question. (Apparently, as is often the case in my reporting career, I had “just missed” whatever bigwig could actually answer these questions.)

During that trip, I would also ask Dr. Mukwege whether such a powder could be real. He said an anesthesiologist had looked into it and couldn’t find anything that was readily available that could put families to sleep, but that it was entirely possible such a thing existed.

I put the question to Bodeli:

Lauren Wolfe: What do you think of the possible use of a “magic powder”?

David Bodeli: It’s possible. I’ve thought about all of it. I met Müller’s wife and asked her what kinds of plants they grew at the plantation. She said that she didn’t know all the herbs there. Someone else could have discovered herbs to put people to sleep. [But it would be difficult to find out.] The plantation is destroyed.

I am a scientific man. Personally, I don’t believe in sorcery, but it’s part of the culture in Africa. I have to believe in something you can actually see. But the people who are doing this believe in it, and this culture is destroying women and children.

There was a night we went to Kavumu after a child had been raped. We found the girl, but her family was in a deep sleep — the children woke up, but the parents were still sleeping. We pushed them to wake them up, but they wouldn’t. We had to carry them out of the house while they were sleeping, and they didn’t wake until 8 a.m. in the police headquarters. This made me think twice.

The second observation I made, and told Dr. Mukwege: The children who were raped, when you meet them, they don’t feel pain from their rape, and sometimes don’t notice that they’re bleeding. They feel it later. By that time, it’s a big wound. So these two things made me believe that there is something the men are using to put the parents and victims in an abnormal state.

I went to pharmacies. At all of them, you can’t find such spray products. If so, all the thieves would use them and they’d be breaking into houses and banks every day. So maybe you can find them somewhere else, but not here. I don’t know all the kinds of medicine or plants.

I’ve been told there is someone who acts as a pastor who was arrested and is now in prison. He made people sleep using plants mixed with water, and they would sleep for 48 hours. He puts them near your nose. And this so-called pastor, he was using this plant to rape women and empty their pockets. It’s not me who arrested him, I’m just telling you this to show you that there is such a plant, but we don’t know what it is. This is one of the possibilities.

While Bodeli can’t say much about the course of the investigation, I ask him, What is the plan moving forward in stopping the men?

Once we have arrested the head, we’ll open the belly of the big snake and that’s when we’ll know who is involved. There are many things I don’t know, but will know soon.

After a few days in Congo (and a few years of investigating from New York), I came into this interview with a single possible perpetrator in mind. I was nearly shaking with anticipation as I reached the moment when I was ready to ask Bodeli whether he agreed with me.

I explained that I had a perpetrator in mind. As the investigating officer, he refused to discuss it.

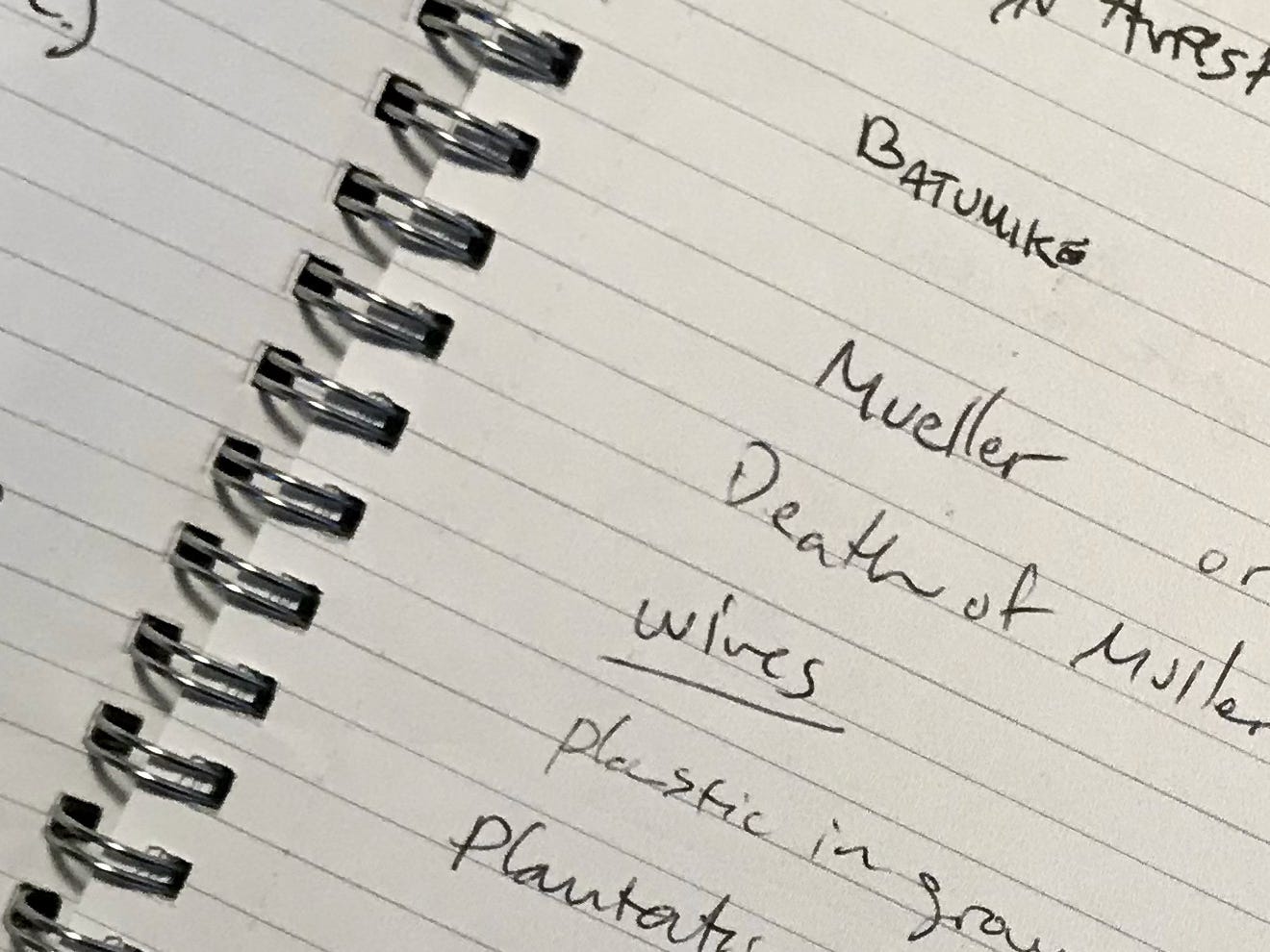

I said that I was going to write down a name in my notebook and show it to him. That he would have to trust me when I said that I would not publish any information that would jeopardize the case he was meticulously building — all that mattered was stopping the attacks. Whatever he said or did would remain sacred between us until he gave me the go-ahead.

I swiped at the mosquitoes biting my legs, and scribbled down a single name: “Batumike” — the legislator and pastor I wrote about here. He was the leader of the men who had killed Walter Müller in 2012 and illegally taken over his Bishiburu plantation.

Even as I write this, my heart flutters as I remember what happened next.

In that dark night over the lake, Bodeli took my notebook into his hands and read the name I had written.

He hunched forward.

A smile slowly condensed the corners of his eyes, and he began to laugh.

Read Part 8 of “How a journalist chases a monster” here.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

Wow...it’s so terrifyingly heartbreaking but the truth needs to come out. Thank you for risking so much. You are a good soul🙏🏼

Ok so now you’ve ended this on a creepy note…fair